There Is Nothing Responsible About Disclosure Of Every Successful Prompt Injection

The InfoSec community is strongest when it can collaborate openly. Few organizations can fend off sophisticated attacks alone—and even they sometimes fail. If we all had to independently discover every malware variant, every vulnerability, every best practice, we wouldn’t get very far. Over time, shared mechanisms emerged: VirusTotal and EDR for malware, CVE for vulnerabilities, standard organizations like OWASP for best practices.

It’s remarkable that we can rely on one another at all. Companies compete fiercely. But their security teams collaborate. That kind of collaboration is not trivial. Nuclear arsenals. Ever-growing marketing budgets. These are places where more collaboration could help—but doesn’t.

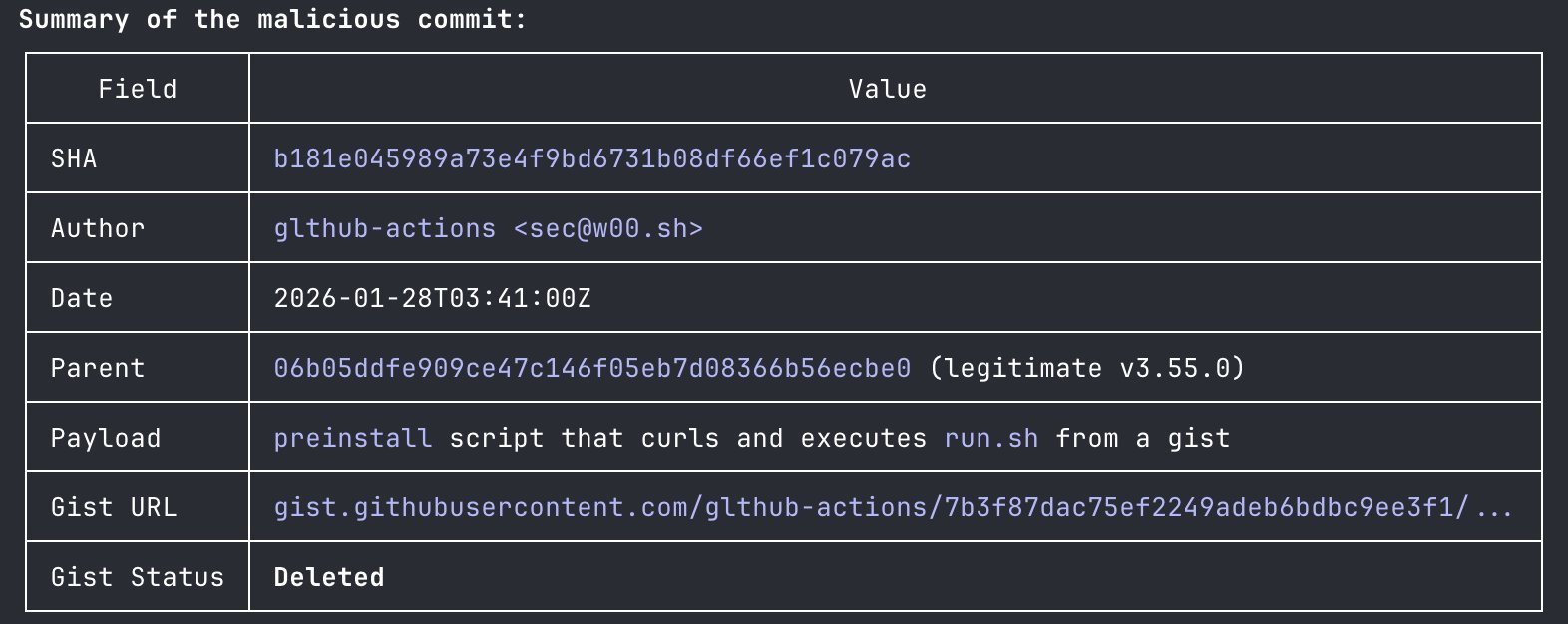

So when attackers hijack AI agents through prompt injection, we fall back on what we know: vulnerability disclosure. Vendors launch responsible disclosure programs (which we applaud). They ask researchers to report successful prompt injections privately. The implicit implication: responsible behavior means private reporting, not public sharing.

But there’s a problem, prompt injection can’t be fixed.

Blocking a specific prompt does little to protect users. It creates an illusion of security that leaves users exposed. Ask any AI security researcher: another prompt will surface—often the same day the last one was blocked.

Calling a vulnerability “fixed” numbs defenders, hiding the deeper issue. Anything your agent can do for you, an attacker can do too—once they take control.

It’s not a bug, it’s a design choice. A tradeoff.

Every AI agent sits somewhere on a spectrum between power and risk. Defenders deserve to know where on that spectrum they are. Open-ended agents like OpenAI Operator and Claude’s Computer Use maximize power, to be used at one’s own peril. AI assistants make different tradeoffs exemplified by their approach to web browsing—each vendor has come up with their own imperfect defense mechanism. Vendors make choices which users are forced to live with.

Prompt injections illustrate those choices. They are not vulnerabilities to be patched. They’re demonstrations. We can’t expect organizations to make informed choices about AI risk without showing visceral examples of what could go wrong. And we can’t expect vendors to hold off powerful capabilities in the name of safety without public scrutiny.

That doesn’t mean vulnerability disclosure has no place in AI. Vendors can make risky choices without realizing it. Mistakes happen. Disclosures should be about the agent’s architecture, not a specific prompt.

Rather than treating prompt injection like a vulnerability, treat it like malware. Malware is an inherent risk of general-purpose operating systems. We don’t treat new malware variants as vulnerabilities. We don’t privately report them to Microsoft or Apple. We publicly share it, as soon as possible, or rather its hash. We don’t claim that malware is “fixed” because one hash made it onto a denylist.

When a vulnerability can be fixed, disclosure helps. But when the risk is inherent to the technology, hiding it only robs users of informed choice.