NeurIPS Poster PureGen: Universal Data Purification for Train-Time Poison Defense via Generative Model Dynamics

Poster

PureGen: Universal Data Purification for Train-Time Poison Defense via Generative Model Dynamics

Omead Pooladzandi · Sunay Bhat · Jeffrey Jiang · Alexander Branch · Gregory Pottie

[ Abstract ]

[ Project Page ]

[ Paper]

[ Slides]

[ Poster]

[ OpenReview]

2024 Poster

Abstract:

Train-time data poisoning attacks threaten machine learning models by introducing adversarial examples during training, leading to misclassification. Current defense methods often reduce generalization performance, are attack-specific, and impose significant training overhead. To address this, we introduce a set of universal data purification methods using a stochastic transform, Ψ(x)Ψ(x), realized via iterative Langevin dynamics of Energy-Based Models (EBMs), Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs), or both. These approaches purify poisoned data with minimal impact on classifier generalization. Our specially trained EBMs and DDPMs provide state-of-the-art defense against various attacks (including Narcissus, Bullseye Polytope, Gradient Matching) on CIFAR-10, Tiny-ImageNet, and CINIC-10, without needing attack or classifier-specific information. We discuss performance trade-offs and show that our methods remain highly effective even with poisoned or distributionally shifted generative model training data.

39027755 · PureGen: Universal Data Purification for Train-Time Poison Defense via Generative Model Dynamics

Next

Cancel

Livestream will start soon!

Livestream has already ended.

Presentation has not been recorded yet!

SlidesLive

- title: PureGen: Universal Data Purification for Train-Time Poison Defense via Generative Model Dynamics

LIVE 0:00/5:29

- Report Issue

- Settings

- Playlists

- Bookmarks

- SubtitlesOff

- Playback rate1 ×

-

QualityAuto (720p)

- Settings

- Debug information

- Serversl-yoda-v3-stream-004-alpha.b-cdn.net

-

Subtitles sizeMedium

-

Bookmarks

- Server

- sl-yoda-v3-stream-004-alpha.b-cdn.net

- sl-yoda-v3-stream-004-beta.b-cdn.net

- 1030663356.rsc.cdn77.org

-

1443389201.rsc.cdn77.org

- Subtitles

- Off

-

English

- Playback rate

- 0.5 ×

- 1 ×

- 1.2 ×

- 1.45 ×

- 1.7 ×

-

2 ×

- Quality

- 234p

- 360p

- 432p

- 720p

- 1080p

-

Auto (720p)

- Subtitles size

- Large

- Medium

-

Small

- Mode

-

Video Slideshow

-

Audio Slideshow

-

Slideshow

- Video

My playlists

Playlist name

Create

Bookmarks

00:00:00

PureGen: Universal Data Purification for Train-Time Poison Defense via Generative Model Dynamics

Slide1/16

- Settings

- Sync diff

-

Quality

- Settings

-

Server

-

Quality

- Server

Chat is not available.

PureGen: Universal Data Purification for Train-Time Poison Defense via Generative Model Dynamics | Read Paper on BytezPureGen: Universal Data Purification for Train-Time Poison Defense via Generative Model Dynamics | Read Paper on Bytez

Devs

Not logged in

PureGen: Universal Data Purification for Train-Time Poison Defense via Generative Model Dynamics 7 months ago

·

NeurIPS

Abstract

Train-time data poisoning attacks threaten machine learning models by introducing adversarial examples during training, leading to misclassification. Current defense methods often reduce generalization performance, are attack-specific, and impose significant training overhead. To address this, we introduce a set of universal data purification methods using a stochastic transform,  , realized via iterative Langevin dynamics of Energy-Based Models (EBMs), Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs), or both. These approaches purify poisoned data with minimal impact on classifier generalization. Our specially trained EBMs and DDPMs provide state-of-the-art defense against various attacks (including Narcissus, Bullseye Polytope, Gradient Matching) on CIFAR-10, Tiny-ImageNet, and CINIC-10, without needing attack or classifier-specific information. We discuss performance trade-offs and show that our methods remain highly effective even with poisoned or distributionally shifted generative model training data.

, realized via iterative Langevin dynamics of Energy-Based Models (EBMs), Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs), or both. These approaches purify poisoned data with minimal impact on classifier generalization. Our specially trained EBMs and DDPMs provide state-of-the-art defense against various attacks (including Narcissus, Bullseye Polytope, Gradient Matching) on CIFAR-10, Tiny-ImageNet, and CINIC-10, without needing attack or classifier-specific information. We discuss performance trade-offs and show that our methods remain highly effective even with poisoned or distributionally shifted generative model training data.

1 Introduction

Large datasets enable modern deep learning models but are vulnerable to data poisoning, where adversaries inject imperceptible poisoned images to manipulate model behavior at test time. Poisons can be created with or without knowledge of the model’s architecture or training settings. As deep learning models grow in capability and usage, securing them against such attacks while preserving accuracy is critical.

Numerous methods of poisoning deep learning systems to create backdoors have been proposed in recent years. These disruptive techniques typically fall into two distinct categories: explicit backdoor, triggered data poisoning, or triggerless poisoning attacks. Triggered attacks conceal an imperceptible trigger pattern in the samples of the training data leading to the misclassification of test-time samples containing the hidden trigger [1, 2, 3, 4]. In contrast, triggerless poisoning attacks involve introducing slight, bounded perturbations to individual images that align them with target images of another class within the feature or gradient space resulting in the misclassification of specific instances without necessitating further modification during inference [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Alternatively, data availability attacks pose a training challenge by preventing model learning at train time, but do not introduce any latent backdoors that can be exploited at inference time [10, 11, 12]. In all these scenarios, poisoned examples often appear benign and correctly labeled making them challenging for observers or algorithms to detect.

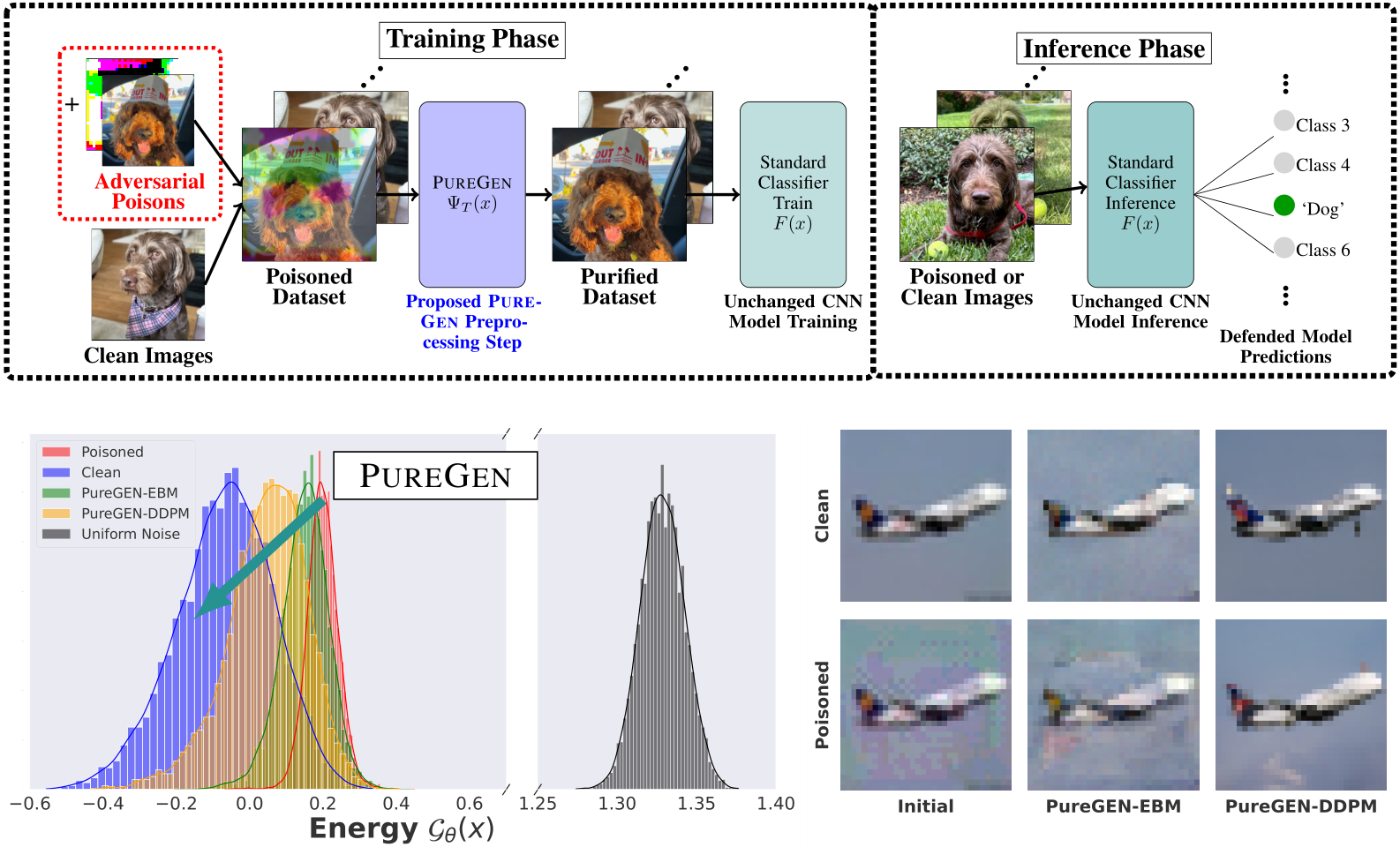

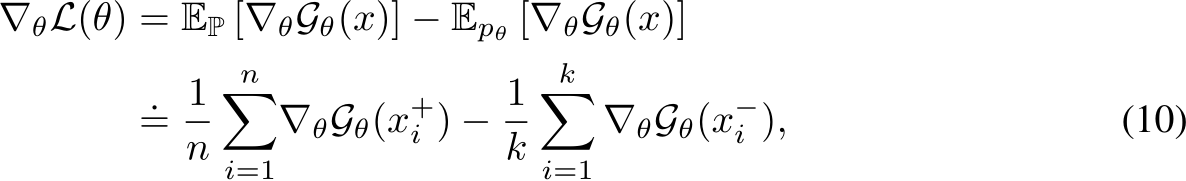

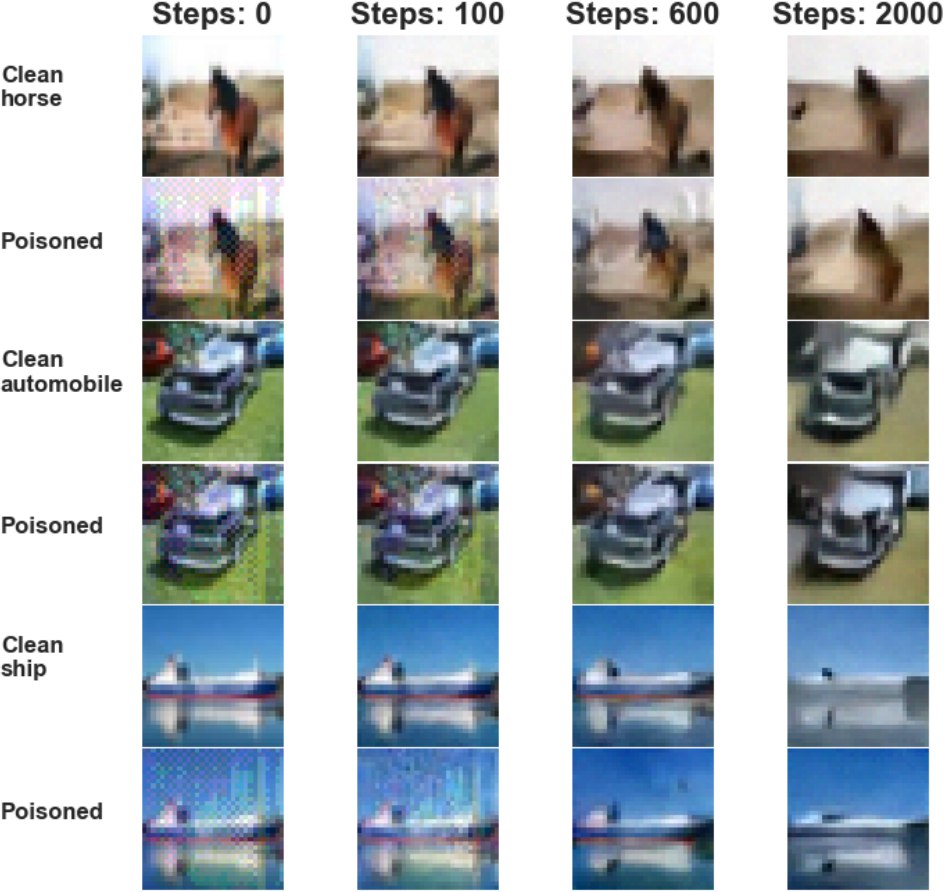

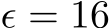

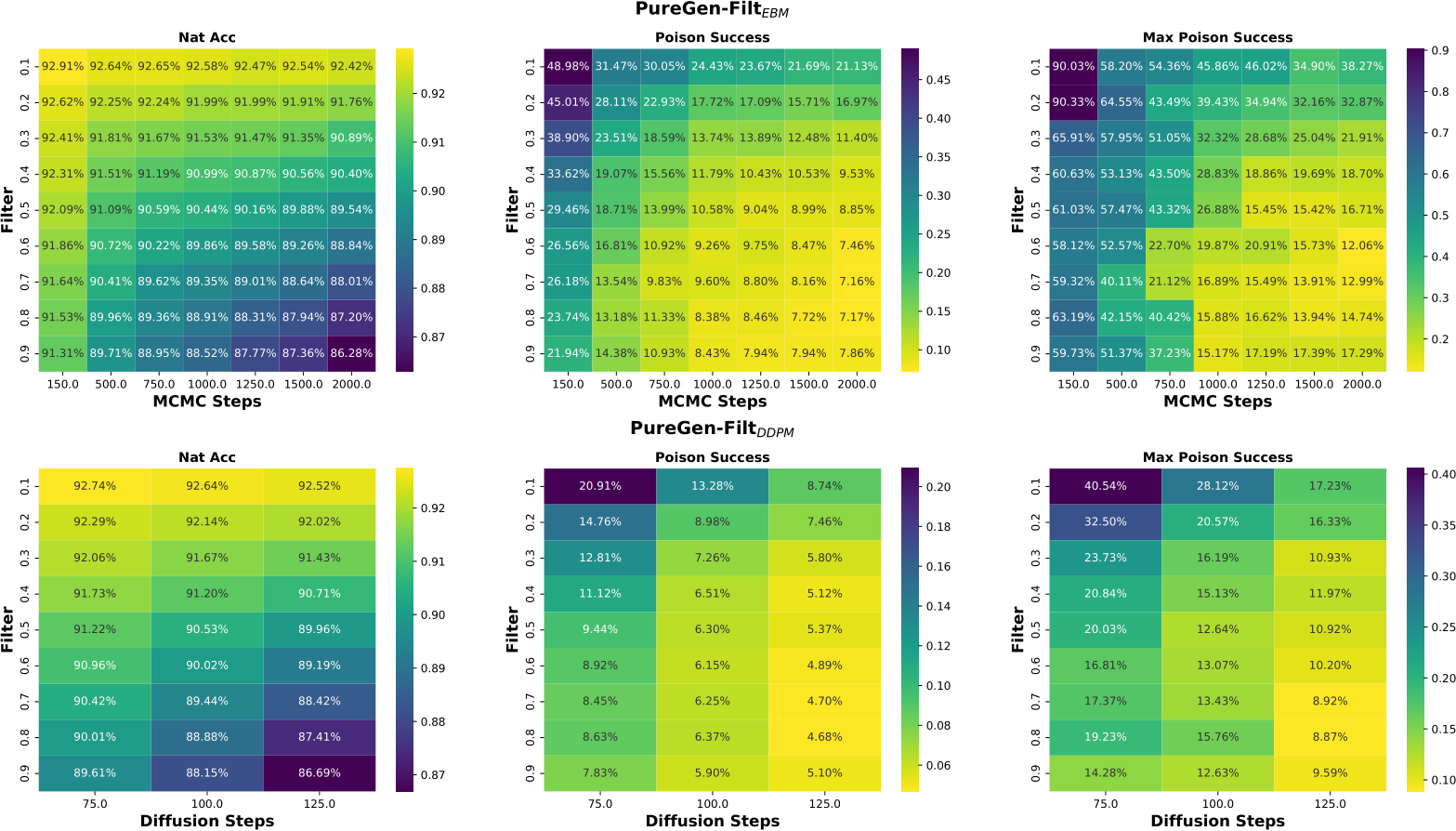

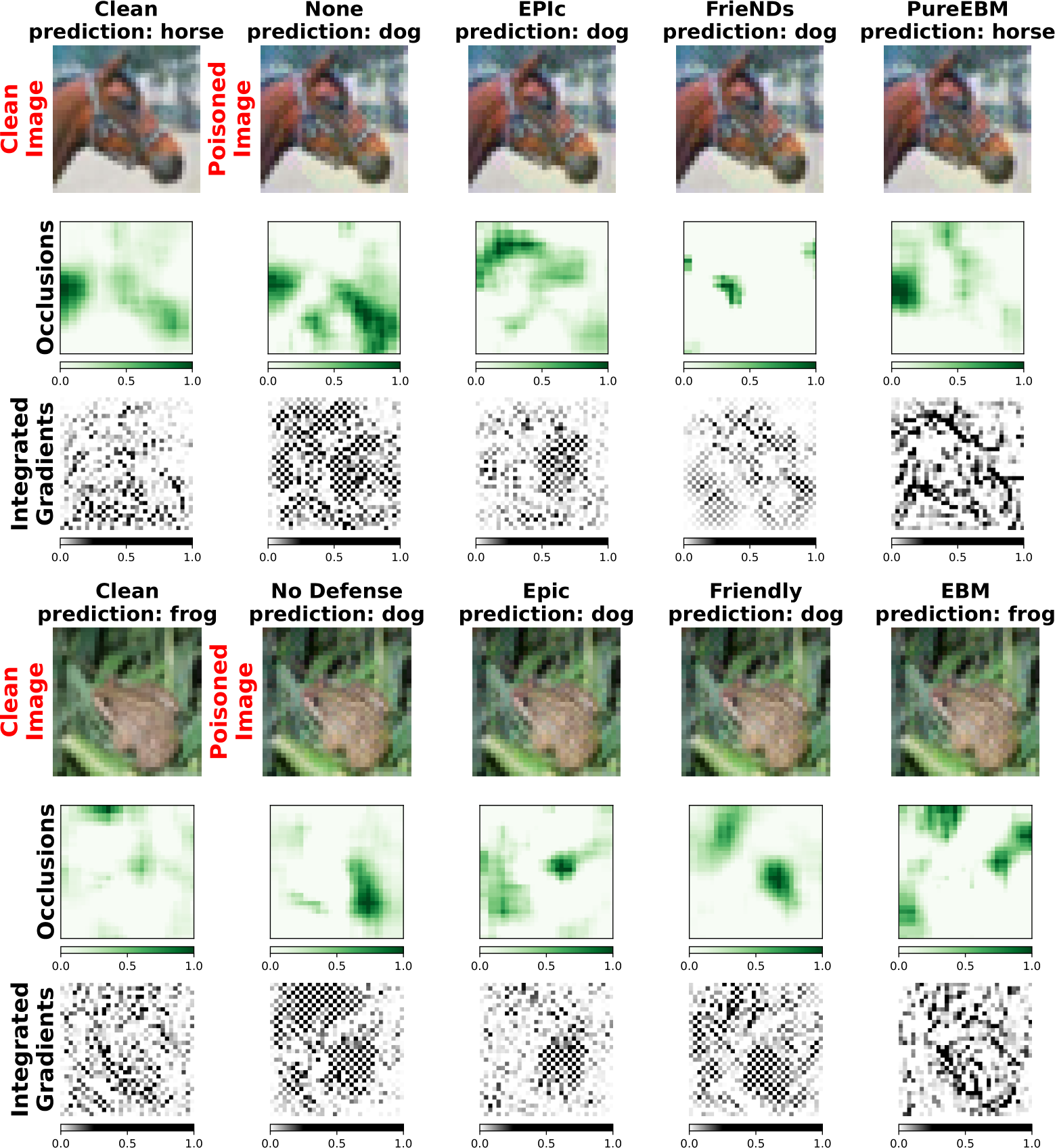

Figure 1: Top The full PUREGEN pipeline is shown where we apply our method as a preprocessing step with no further downstream changes to the classifier training or inference. Poisoned images are moderately exaggerated to show visually. Bottom Left Energy distributions of clean, poisoned, and PUREGEN purified images. Our methods push poisoned images via purification into the natural,clean image energy manifold. Bottom Right The removal of poison artifacts and the similarity of clean and poisoned images after purification using PUREGEN EBM and DDPM dynamics. The purified dataset results in SoTA defense and high classifier natural accuracy.

Current defense strategies against data poisoning exhibit significant limitations. While some methods rely on anomaly detection through techniques such as nearest neighbor analysis, training loss minimization, singular-value decomposition, feature activation or gradient clustering [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19], others resort to robust training strategies including data augmentation, randomized smoothing, ensembling, adversarial training and maximal noise augmentation [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. However, these approaches either undermine the model’s generalization performance [27, 18], offer protection only against specific attack types [27, 17, 15], or prove computationally prohibitive for standard deep learning workflows [22, 16, 28, 18, 27, 17, 26]. There remains a critical need for more effective and practical defense mechanisms in the realm of deep learning security.

Generative models have been used for robust/adversarial training, but not for train-time backdoor attacks, to the best of our knowledge. Recent works have demonstrated the effectiveness of both EBM dynamics and Diffusion models to purify datasets against inference or availability attacks [29, 30, 31], but train-time backdoor attacks present additional challenges in both evaluation and application, requiring training using Public Out-of-Distribution (POOD) datasets and methods to avoid cumbersome computation or setup for classifier training.

We propose PUREGEN, a set of powerful stochastic preprocessing defense techniques,  , against train-time poisoning attacks. PUREGEN-EBM uses EBM-guided Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to purify poisoned images, while PUREGEN-DDPM uses a limited forward/reverse diffusion process, specifically for purification. Training DDPM models on a subset of the noise schedule improves purification by dedicating more model capacity to ‘restoration’ rather than generation. We further find that the energy of poisoned images is significantly higher than the baseline images, for a trained EBM, and PUREGEN techniques move poisoned samples to a lower-energy, natural data manifold with minimal accuracy loss. The PUREGEN pipeline, sample energy distributions, and purification on a sample image can be seen in Figure 1. PUREGEN significantly outperforms current defenses in all tested scenarios. Our key contributions in this work are as follows.

, against train-time poisoning attacks. PUREGEN-EBM uses EBM-guided Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to purify poisoned images, while PUREGEN-DDPM uses a limited forward/reverse diffusion process, specifically for purification. Training DDPM models on a subset of the noise schedule improves purification by dedicating more model capacity to ‘restoration’ rather than generation. We further find that the energy of poisoned images is significantly higher than the baseline images, for a trained EBM, and PUREGEN techniques move poisoned samples to a lower-energy, natural data manifold with minimal accuracy loss. The PUREGEN pipeline, sample energy distributions, and purification on a sample image can be seen in Figure 1. PUREGEN significantly outperforms current defenses in all tested scenarios. Our key contributions in this work are as follows.

• A set of state-of-the-art (SoTA) stochastic preprocessing defenses  against adversarial poisons using MCMC dynamics of EBMs and DDPMs trained specifically for purification

against adversarial poisons using MCMC dynamics of EBMs and DDPMs trained specifically for purification

named PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM with analysis providing further intuition on effectiveness

• Experimental results showing the broad application of  with minimal tuning and no prior knowledge needed of the poison type and classification model

with minimal tuning and no prior knowledge needed of the poison type and classification model

• Results showing SoTA performance can be maintained even when PUREGEN models’ training data includes poisons or is from a significantly different distribution than the classifier/attacked train data distribution

• Results showing even further performance gains from combinations of PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM and robustness to defense-aware poisons

2 Related Work

2.1 Targeted Data Poisoning Attack

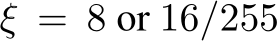

Poisoning of a dataset occurs when an attacker injects small adversarial perturbations  (where

(where  and typically

and typically  ) into a small fraction,

) into a small fraction,  , of training images, making poisoning incredibly difficult to detect. These train-time attacks introduce local sharp regions with a considerably higher training loss [26]. A successful attack occurs when, after SGD optimizes the cross-entropy training objective on these poisoned datasets, invisible backdoor vulnerabilities are baked into a classifier, without a noticeable change in overall test accuracy. This is in contrast to inference-time or other adversarial scenarios where an attacker might be defense or model-aware. The goal in train-time attacks is “stealth” via minimal impact to the dataset and training and testing curves while creating backdoors to exploit at deployment.

, of training images, making poisoning incredibly difficult to detect. These train-time attacks introduce local sharp regions with a considerably higher training loss [26]. A successful attack occurs when, after SGD optimizes the cross-entropy training objective on these poisoned datasets, invisible backdoor vulnerabilities are baked into a classifier, without a noticeable change in overall test accuracy. This is in contrast to inference-time or other adversarial scenarios where an attacker might be defense or model-aware. The goal in train-time attacks is “stealth” via minimal impact to the dataset and training and testing curves while creating backdoors to exploit at deployment.

In the realm of deep network poison security, we encounter two primary categories of attacks: triggered and triggerless attacks. Triggered attacks, often referred to as backdoor attacks, involve contaminating a limited number of training data samples with a specific trigger (often a patch)  (similarly constrained

(similarly constrained  ) that corresponds to a target label,

) that corresponds to a target label,  . After training, a successful backdoor attack misclassifies when the perturbation

. After training, a successful backdoor attack misclassifies when the perturbation

Early backdoor attacks were characterized by their use of non-clean labels [32, 1, 33, 3], but more recent iterations of backdoor attacks have evolved to produce poisoned examples that lack a visible trigger [2,34,4].

On the other hand, triggerless poisoning attacks involve the addition of subtle adversarial perturbations to base images  , aiming to align their feature representations or gradients with those of target images of another class, causing target misclassification [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. These poisoned images are virtually undetectable by external observers. Remarkably, they do not necessitate any alterations to the target images or labels during the inference stage. For a poison targeting a group of target images

, aiming to align their feature representations or gradients with those of target images of another class, causing target misclassification [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. These poisoned images are virtually undetectable by external observers. Remarkably, they do not necessitate any alterations to the target images or labels during the inference stage. For a poison targeting a group of target images  to be misclassified as

to be misclassified as  , an ideal triggerless attack would produce a resultant function:

, an ideal triggerless attack would produce a resultant function:

Background for data availability attacks can be found in [35]. We include results for one leading data availability attack Neural Tangent Gradient Attack (NTGA) [12], but we do not focus on such attacks since they are realized in model results during training. They do not pose a latent security risk in deployed models, and arguably have ethical applications within data privacy and content creator protections as discussed in App. 6.

The current leading poisoning attacks that we assess our defense against are listed below. More details about their generation can be found in App. A.1.

• Bullseye Polytope (BP): BP crafts poisoned samples that position the target near the center of their convex hull in a feature space [9].

• Gradient Matching (GM): GM generates poisoned data by approximating a bi-level objective by aligning the gradients of clean-label poisoned data with those of the adversariallylabeled target [8]. This attack has shown effectiveness against data augmentation and differential privacy.

• Narcissus (NS): NS is a clean-label backdoor attack that operates with minimal knowledge of the training set, instead using a larger natural dataset, evading state-of-the-art defenses by synthesizing persistent trigger features for a given target class. [4].

• Neural Tangent Generalization Attacks (NTGA): NTGA is a clean-label, black-box data availability attack that can collapse model test accuracy [12].

2.2 Train-Time Poison Defense Strategies

Poison defense categories broadly take two primary approaches: filtering and robust training techniques. Filtering methods identify outliers in the feature space through methods such as thresholding [14], nearest neighbor analysis [17], activation space inspection [16], or by examining the covariance matrix of features [15]. These defenses often assume that only a small subset of the data is poisoned, making them vulnerable to attacks involving a higher concentration of poisoned points. Furthermore, these methods substantially increase training time, as they require training with poisoned data, followed by computationally expensive filtering and model retraining [16,17,14,15].

On the other hand, robust training methods involve techniques like randomized smoothing [20], extensive data augmentation [36], model ensembling [21], gradient magnitude and direction constraints [37], poison detection through gradient ascent [24], and adversarial training [27, 28, 25]. Additionally, differentially private (DP) training methods have been explored as a defense against data poisoning [22, 38]. Robust training techniques often require a trade-off between generalization and poison success rate [22, 37, 24, 28, 25, 26] and can be computationally intensive [27, 28]. Some methods use optimized noise constructed via Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) or Stochastic Gradient Descent methods to make noise that defends against attacks [39,26].

Recently Yang et al. [2022] proposed EPIC, a coreset selection method that rejects poisoned images that are isolated in the gradient space while training, and Liu et al. [2023] proposed FRIENDS, a per-image preprocessing transformation that solves a min-max problem to stochastically add

-bound ‘friendly noise’ (typically 16/255) to combat adversarial perturbations (of 8/255) [18,26].

-bound ‘friendly noise’ (typically 16/255) to combat adversarial perturbations (of 8/255) [18,26].

These two methods are the previous SoTA and will serve as a benchmark for our PUREGEN methods in the experimental results. Finally, simple compression JPEG has been shown to defend against a variety of other adversarial attacks, and we apply it as a baseline defense in train-time poison attacks here as well, finding that it often outperforms previous SoTA methods [40].

3 PUREGEN: Purifying Generative Dynamics against Poisoning Attacks

3.1 Energy-Based Models and PUREGEN-EBM

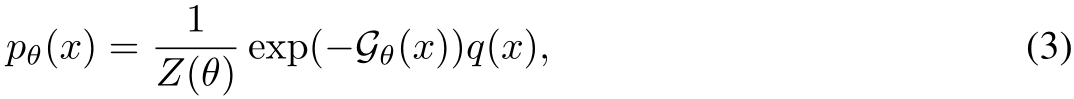

An Energy-Based Model (EBM) is formulated as a Gibbs-Boltzmann density, as introduced in [41]. This model can be mathematically represented as:

where  denotes an image signal, and q(x) is a reference measure, often a uniform or standard normal distribution. Here,

denotes an image signal, and q(x) is a reference measure, often a uniform or standard normal distribution. Here,  signifies the energy potential, parameterized by a ConvNet with parameters

signifies the energy potential, parameterized by a ConvNet with parameters

The EBM  can be interpreted as an unnormalized probability of how natural the image is to the dataset. Thus, we can use

can be interpreted as an unnormalized probability of how natural the image is to the dataset. Thus, we can use  to filter images based on their likelihood of being poisoned. Furthermore, the EBM can be used as a generator. Given a starting clear or purified image

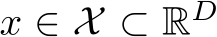

to filter images based on their likelihood of being poisoned. Furthermore, the EBM can be used as a generator. Given a starting clear or purified image  Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Langevin dynamics to iteratively generate more natural images via Equation 4.

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Langevin dynamics to iteratively generate more natural images via Equation 4.

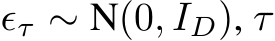

where  indexes the time step of the Langevin dynamics, and

indexes the time step of the Langevin dynamics, and  is the discretization of time [41].

is the discretization of time [41].  can be obtained by back-propagation. Intuitively, the EBM informs a noisy stochastic gradient descent toward natural images. More details on the convergent contrastive learning mechanism of the EBM and mid-run generative dynamics that makes purification possible can be found in App. A.2.1. Ultimately, the training modifications of using realistic images to initialize the MCMC runs of negative samples produces mid-run, meta-stable EBM dynamics which can be leveraged for better purification. Further intuition is in Section 3.4.

can be obtained by back-propagation. Intuitively, the EBM informs a noisy stochastic gradient descent toward natural images. More details on the convergent contrastive learning mechanism of the EBM and mid-run generative dynamics that makes purification possible can be found in App. A.2.1. Ultimately, the training modifications of using realistic images to initialize the MCMC runs of negative samples produces mid-run, meta-stable EBM dynamics which can be leveraged for better purification. Further intuition is in Section 3.4.

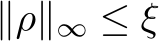

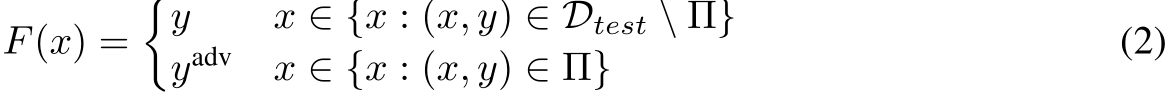

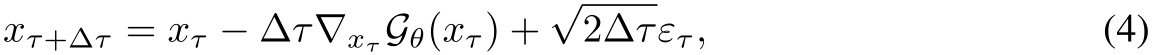

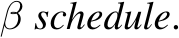

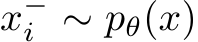

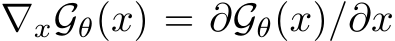

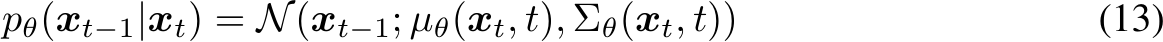

3.2 Diffusion Models and PUREGEN-DDPM

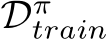

Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) are a class of generative models proposed by [Ho et al., 2020] where the key idea is to define a forward diffusion process that adds noise until the image reaches a noise prior and then learn a reverse process that removes noise to generate samples as discussed further in App. A.3[42]. For purification, we are interested in the stochastic “restoration” of the reverse process, where the forward process can degrade the image enough to remove adversarial perturbations. We find that only training the DDPM with a subset of the standard  schedule, where the original image never reaches the prior, sacrifices generative capabilities for slightly improved poison defense while reducing training costs. Thus we introduce PUREGEN-DDPM which makes the simple adjustment of only training DDPMs for an initial portion of the standard forward process, improving purification capabilities. For our experiments, we find models trained up to 250 steps outperformed models in terms of poison purification than those trained on higher steps, up to the standard 1000 steps. We show visualizations and empirical evidence of this in Figure 2 below. In App. E.2.2 we show that pre-trained, standard DDPMs can offer comparable defense performance, but with added training cost.

schedule, where the original image never reaches the prior, sacrifices generative capabilities for slightly improved poison defense while reducing training costs. Thus we introduce PUREGEN-DDPM which makes the simple adjustment of only training DDPMs for an initial portion of the standard forward process, improving purification capabilities. For our experiments, we find models trained up to 250 steps outperformed models in terms of poison purification than those trained on higher steps, up to the standard 1000 steps. We show visualizations and empirical evidence of this in Figure 2 below. In App. E.2.2 we show that pre-trained, standard DDPMs can offer comparable defense performance, but with added training cost.

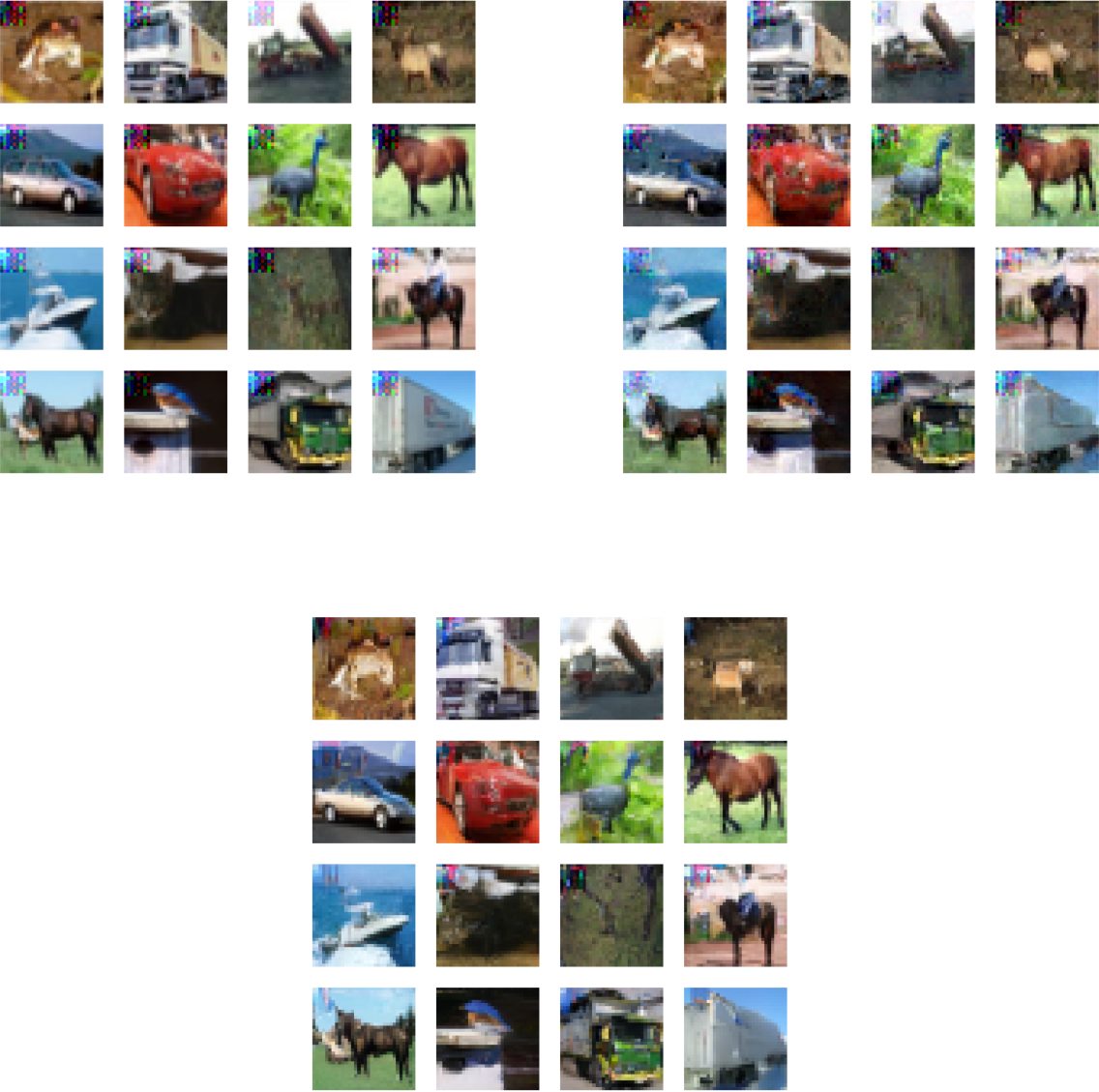

Figure 2: Top We compare PUREGEN-DDPM forward steps with the standard DDPM where 250 steps degrades images for purification but does not reach a noise prior. Note that all model are trained with the same linear  Bottom Left Generated images from models with 250, 750, and 1000 (Standard) train forward steps where it is clear 250 steps does not generate realistic images Bottom Right Significantly improved poison defense performance of PUREGEN-DDPM with 250 train steps indicating a trade-off between data purification and generative capabilities.

Bottom Left Generated images from models with 250, 750, and 1000 (Standard) train forward steps where it is clear 250 steps does not generate realistic images Bottom Right Significantly improved poison defense performance of PUREGEN-DDPM with 250 train steps indicating a trade-off between data purification and generative capabilities.

3.3 Classification with Stochastic Transformation

Let  be a stochastic pre-processing transformation. In this work,

be a stochastic pre-processing transformation. In this work,  , is the random variable of a fixed image x, and we define

, is the random variable of a fixed image x, and we define  , hyperparameters specifying the number of EBM MCMC steps, the number of diffusion steps, and the number of times these steps are repeated, respectively. Then,

, hyperparameters specifying the number of EBM MCMC steps, the number of diffusion steps, and the number of times these steps are repeated, respectively. Then,  and

and

We compose a stochastic transformation  with a randomly initialized deterministic classifier

with a randomly initialized deterministic classifier  (for us, a naturally trained classifier) to define a new deterministic classifier

(for us, a naturally trained classifier) to define a new deterministic classifier  as

as

which is trained with cross-entropy loss via SGD to realize  . As this is computationally infeasible we take

. As this is computationally infeasible we take  as the point estimate of

as the point estimate of  , which is valid because

, which is valid because  low variance.

low variance.

3.4 Erasing Poison Signals via Mid-Run MCMC

The stochastic transform  is an iterative process. PUREGEN-EBM is akin to a noisy gradient descent over the unconditional energy landscape of a learned data distribution. This is more implicit in the PUREGEN-DDPM dynamics. As T increases, poisoned images move from their initial higher energy towards more realistic lower-energy samples that lack poison perturbations. As shown in Figure 1, the energy distributions of poisoned images are much higher, pushing the poisons away from the likely manifold of natural images. By using Langevin dynamics of EBMs and DDPMs, we transport poisoned images back toward the center of the energy basin.

is an iterative process. PUREGEN-EBM is akin to a noisy gradient descent over the unconditional energy landscape of a learned data distribution. This is more implicit in the PUREGEN-DDPM dynamics. As T increases, poisoned images move from their initial higher energy towards more realistic lower-energy samples that lack poison perturbations. As shown in Figure 1, the energy distributions of poisoned images are much higher, pushing the poisons away from the likely manifold of natural images. By using Langevin dynamics of EBMs and DDPMs, we transport poisoned images back toward the center of the energy basin.

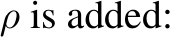

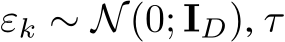

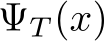

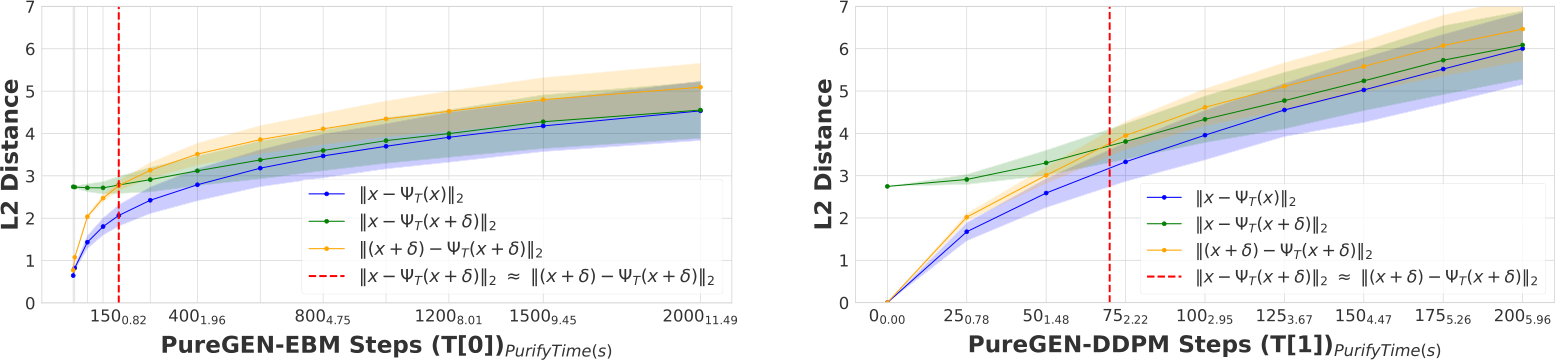

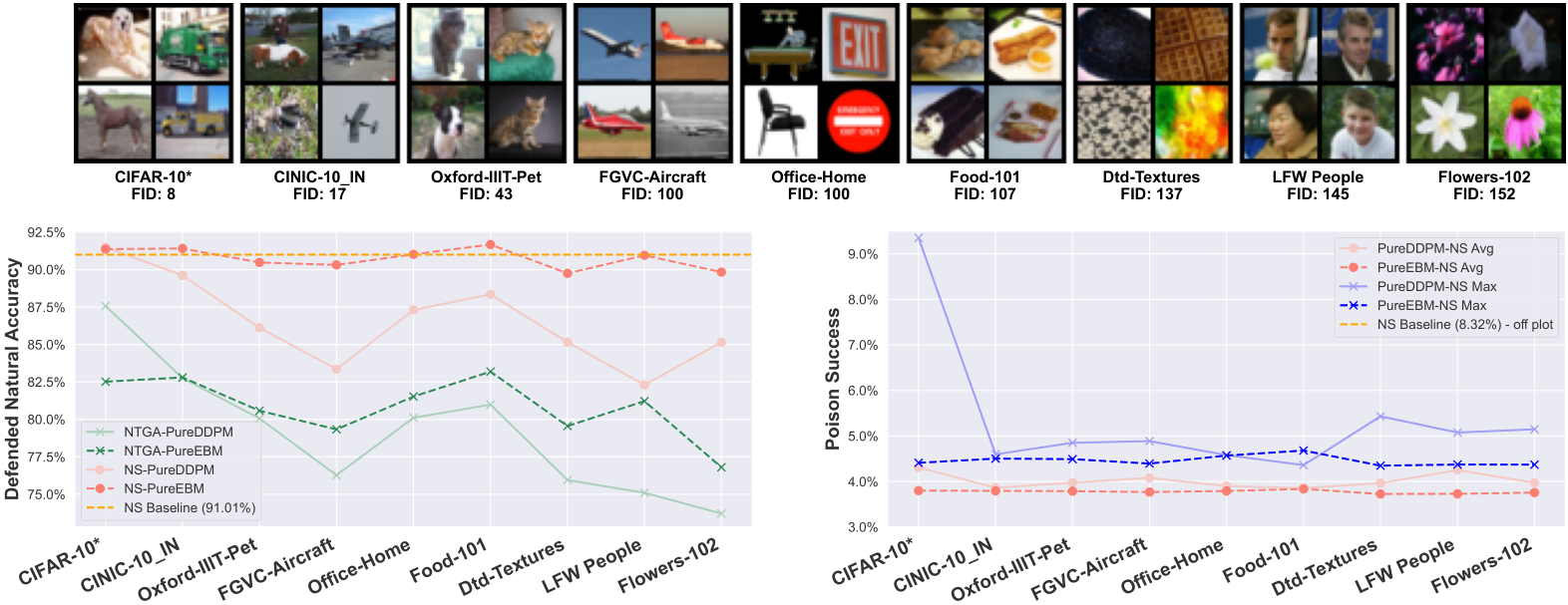

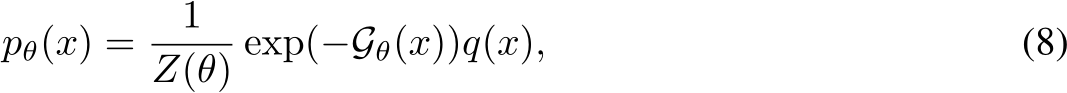

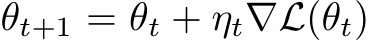

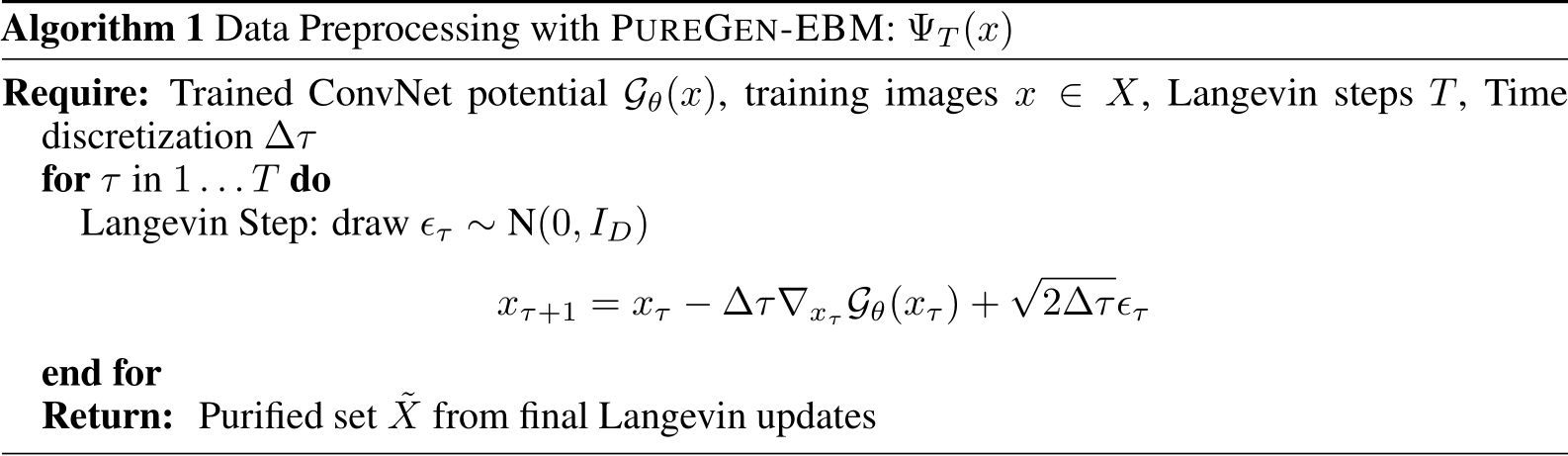

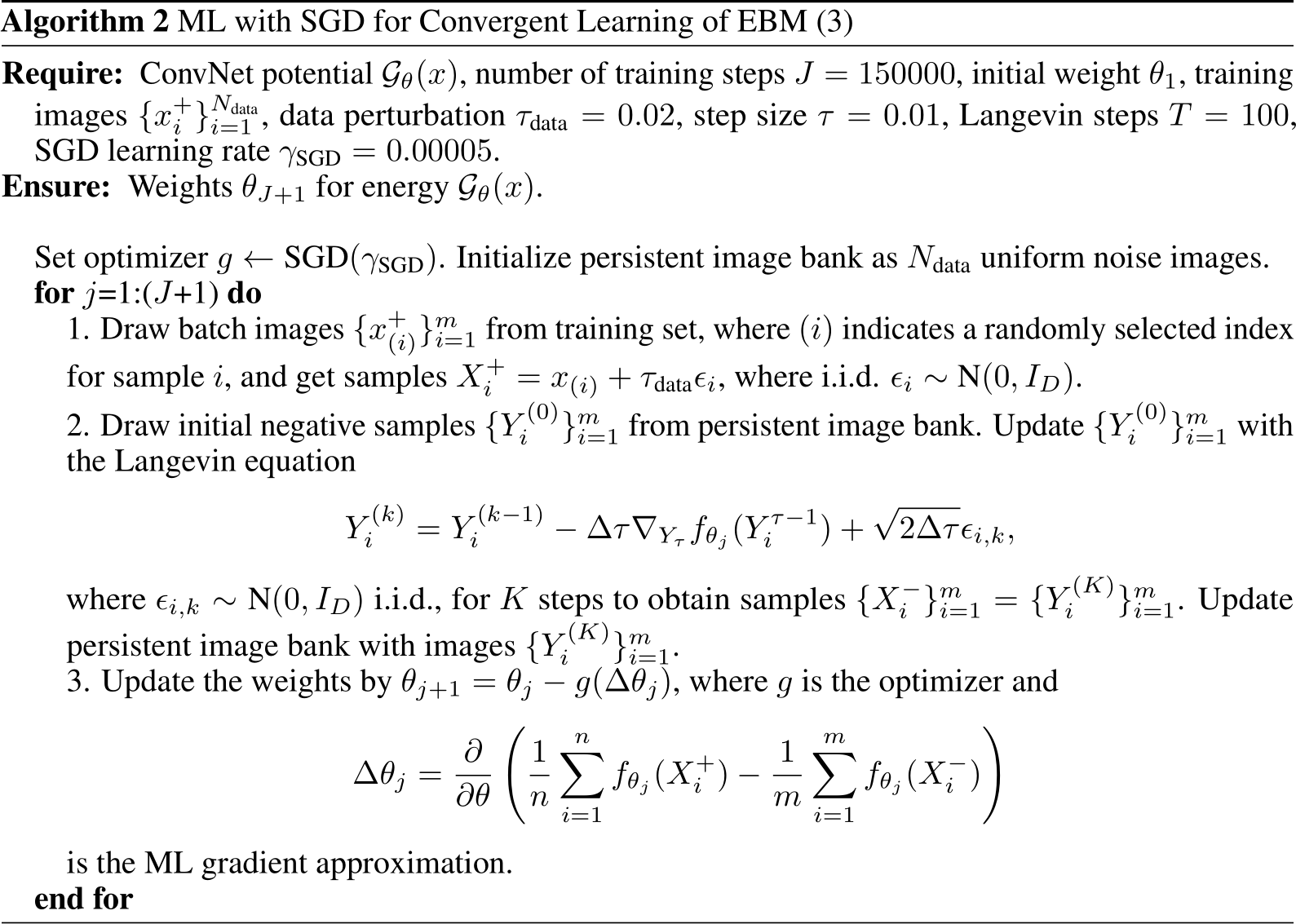

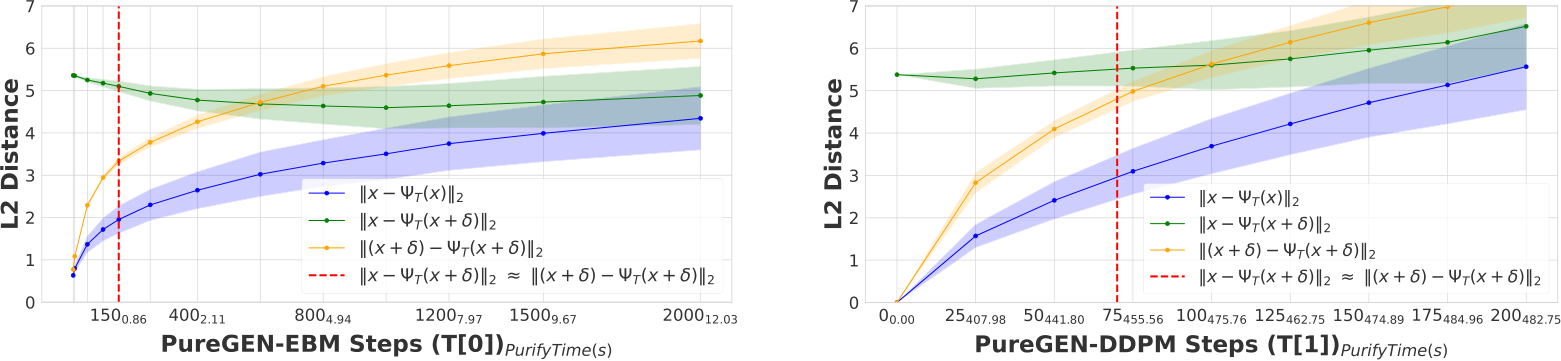

Figure 3: Plot of  distances for PUREGEN-EBM (Left) and PUREGEN-DDPM (Right) between clean images and clean purified (blue), clean images and poisoned purified (green), and poisoned images and poisoned purified images (orange) at points on the Langevin dynamics trajectory. Purifying poisoned images for less than 250 steps moves a poisoned image closer to its clean image with a minimum around 150, preserving the natural image while removing the adversarial features.

distances for PUREGEN-EBM (Left) and PUREGEN-DDPM (Right) between clean images and clean purified (blue), clean images and poisoned purified (green), and poisoned images and poisoned purified images (orange) at points on the Langevin dynamics trajectory. Purifying poisoned images for less than 250 steps moves a poisoned image closer to its clean image with a minimum around 150, preserving the natural image while removing the adversarial features.

In from-scratch  poison scenarios, 150 EBM Langevin steps or 75 DDPM steps fully purifies the majority of the dataset with minimal feature loss to the original image. In Figure 3, we explore the Langevin trajectory’s impacts on

poison scenarios, 150 EBM Langevin steps or 75 DDPM steps fully purifies the majority of the dataset with minimal feature loss to the original image. In Figure 3, we explore the Langevin trajectory’s impacts on  distance of both purified clean and poisoned images from the initial clean image (

distance of both purified clean and poisoned images from the initial clean image ( and

and  ), and the purified poisoned image’s trajectory away from its poisoned starting point (

), and the purified poisoned image’s trajectory away from its poisoned starting point ( ). Both poisoned and clean distance trajectories converge to similar distances away from the original clean image (

). Both poisoned and clean distance trajectories converge to similar distances away from the original clean image (

), and the intersection where

), and the intersection where

(indicated by the dotted red line), occurs at

(indicated by the dotted red line), occurs at  150 EBM and 75 DDPM steps, indicating when purification has moved the poisoned image closer to the original clean image than the poisoned version of the image.

150 EBM and 75 DDPM steps, indicating when purification has moved the poisoned image closer to the original clean image than the poisoned version of the image.

These dynamics provide a concrete intuition for choosing step counts that best balance poison defense with natural accuracy (given a poison  ), hence why we use 150-1000 EBM steps of 75-125 (specifically 150 EBM, 75 DDPM steps in from-scratch scenarios) shown in App. D.2. Further, PUREGEN-EBM dynamics stay closer to the original images, while PUREGEN-DDPM moves further away as we increase the steps as the EBM has explicitly learned a probable data distribution, while the DDPM restoration is highly dependent on the conditional information in the degraded image. More experiments comparing the two are shown in App. G.2. These dynamics align with empirical results showing that EBMs better maintain natural accuracy and poison defense with smaller perturbations and across larger distributional shifts, but DDPM dynamics are better suited for larger poison perturbations. Finally, we note the purify times in the x-axes of Fig. 3, where PUREGEN-EBM is much faster for the same step counts to highlight the computational differences for the two methods, which we further explore Section 4.5.

), hence why we use 150-1000 EBM steps of 75-125 (specifically 150 EBM, 75 DDPM steps in from-scratch scenarios) shown in App. D.2. Further, PUREGEN-EBM dynamics stay closer to the original images, while PUREGEN-DDPM moves further away as we increase the steps as the EBM has explicitly learned a probable data distribution, while the DDPM restoration is highly dependent on the conditional information in the degraded image. More experiments comparing the two are shown in App. G.2. These dynamics align with empirical results showing that EBMs better maintain natural accuracy and poison defense with smaller perturbations and across larger distributional shifts, but DDPM dynamics are better suited for larger poison perturbations. Finally, we note the purify times in the x-axes of Fig. 3, where PUREGEN-EBM is much faster for the same step counts to highlight the computational differences for the two methods, which we further explore Section 4.5.

Ultimately, one can think of PureGen as sampling from a “close” region in the pixel space around the original image where proximity is determined by a stochastic process that is initialized at the image and remains “close” due to an explicit (EBM) or implicit (DDPM) energy gradient - all but assuring the original poison is mitigated in the process.

4 Experiments

4.1 Experimental Details

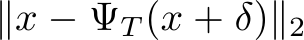

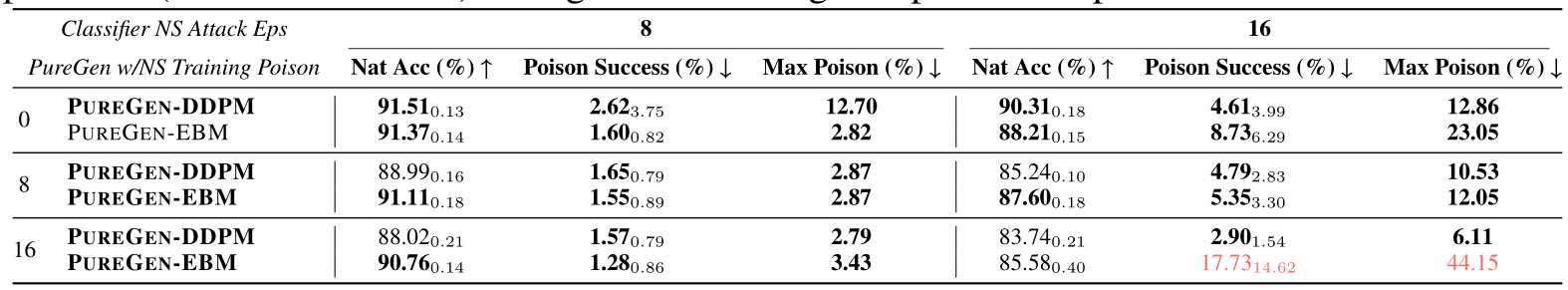

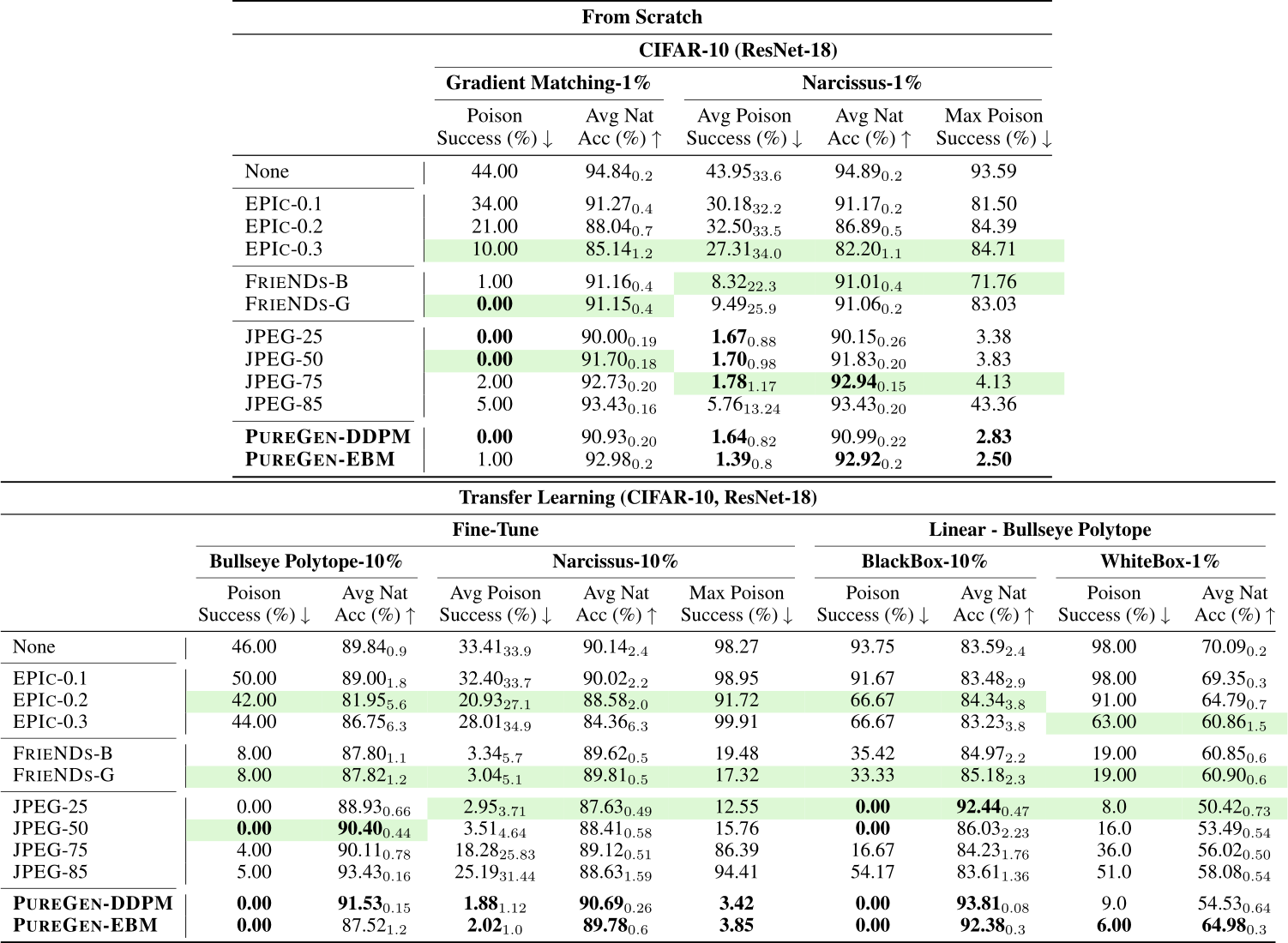

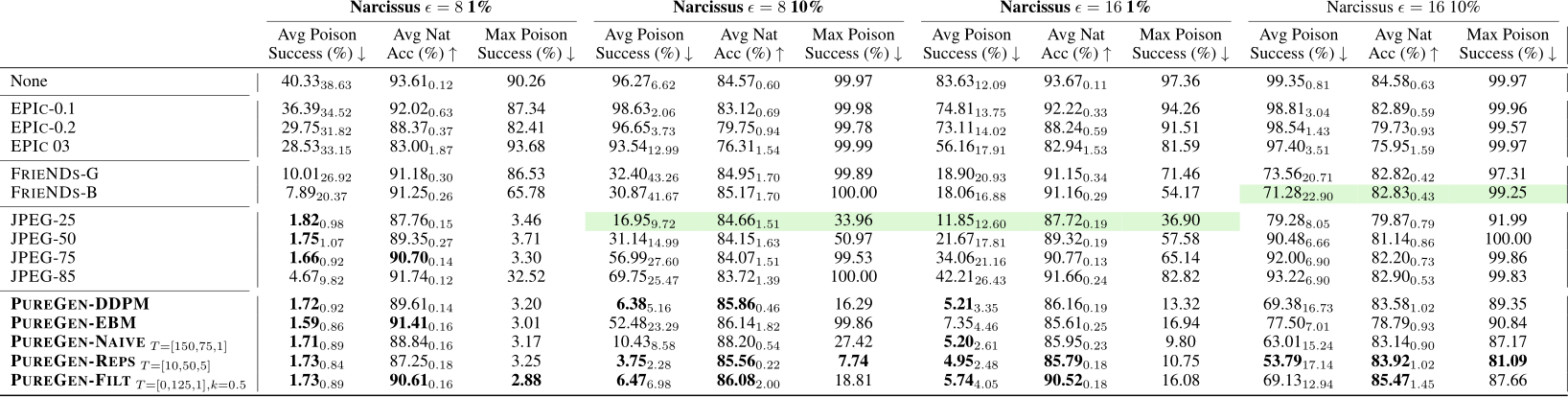

Table 1: Poison success and natural accuracy in all ResNet poison training scenarios. We report the mean and the standard deviations (as subscripts) of 100 GM experiments, 50 BP experiments, and NS triggers over 10 classes.

We evaluate PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM against state-of-the-art defenses EPIC and FRIENDS, and baseline defense JPEG, on leading poisons Narcissus (NS), Gradient Matching (GM), and Bullseye Polytope (BP). Using ResNet18 and CIFAR-10, we measure poison success, natural accuracy, and max poison success across classes for triggered NS attacks. All poisons and poison scenario settings come from previous baseline attack and defense works, and additional details on poison sources, poison crafting, definitions of poison success, and training hyperparameters can be found in App. D. Poisons were chosen for their availability or ease of generation from the poisoncrafting research community, which is why there are no GM results on CINIC-10 and no Narcissus results on Tiny-ImageNet. And we note that certain poison successes (GM and BP) are for moving a single image to a target class per 50-100 classifier scenarios and, hence, lack a standard deviation. Athough, we show the results are low variance using different seeds on a subset of scenarios in App. E.2.3.

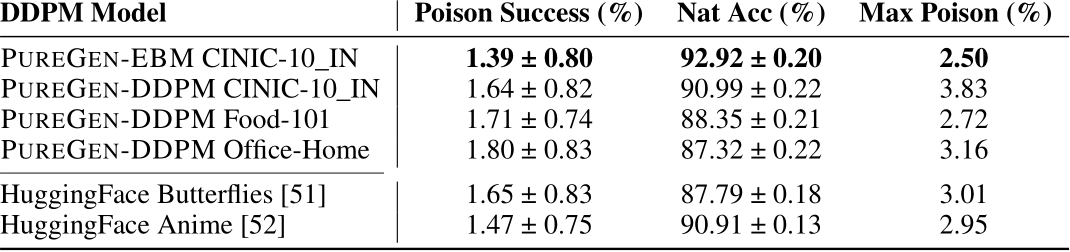

Our EBMs and DDPMs are trained on the ImageNet (70k) portion of the CINIC-10 dataset, CIFAR-10, and CalTech-256 for poisons scenarios using CIFAR-10, CINIC-10, and Tiny-ImageNet respectively, to ensure no overlap of PUREGEN train and attacked classifier train datasets [43, 44,45].

4.2 Benchmark Results

Table 1 shows our primary results using ResNet18 (34 for Tiny-IN) in which PUREGEN achieves state-of-the-art (SoTA) poison defense and natural accuracy in all poison scenarios. Both PUREGEN methods show large improvements over baselines in triggered NS attacks (PUREGEN matches or exceeds previous SoTA with a 1-6% poison defense reduction and 0.5-1.5% less degradation in natural accuracy), while maintaining perfect or near-perfect defense with improved natural accuracy in triggerless BP and GM scenarios. Note that PUREGEN-EBM does a better job maintaining natural accuracy in the 100 class scenarios (BP-WhiteBox and Tiny-IN), while PUREGEN-DDPM tends to get much better poison defense when the PUREGEN-EBM is not already low.

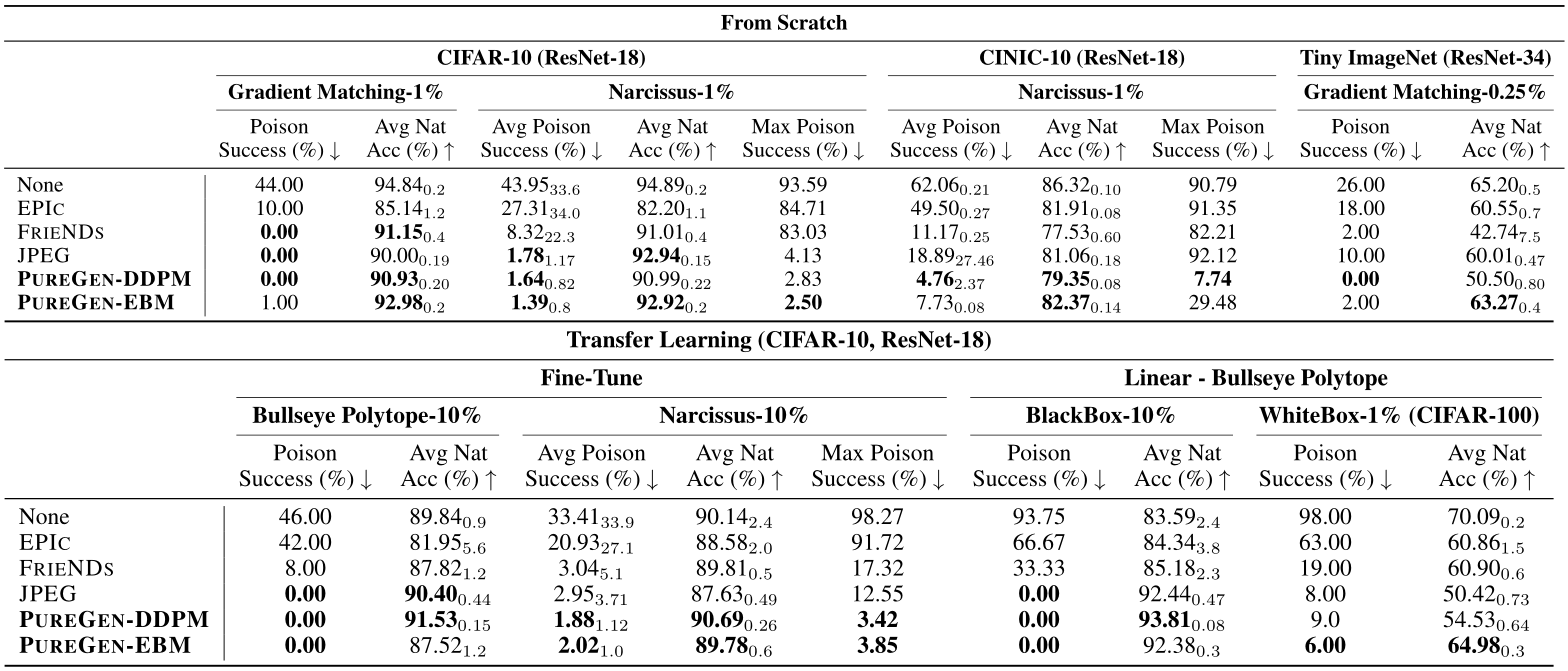

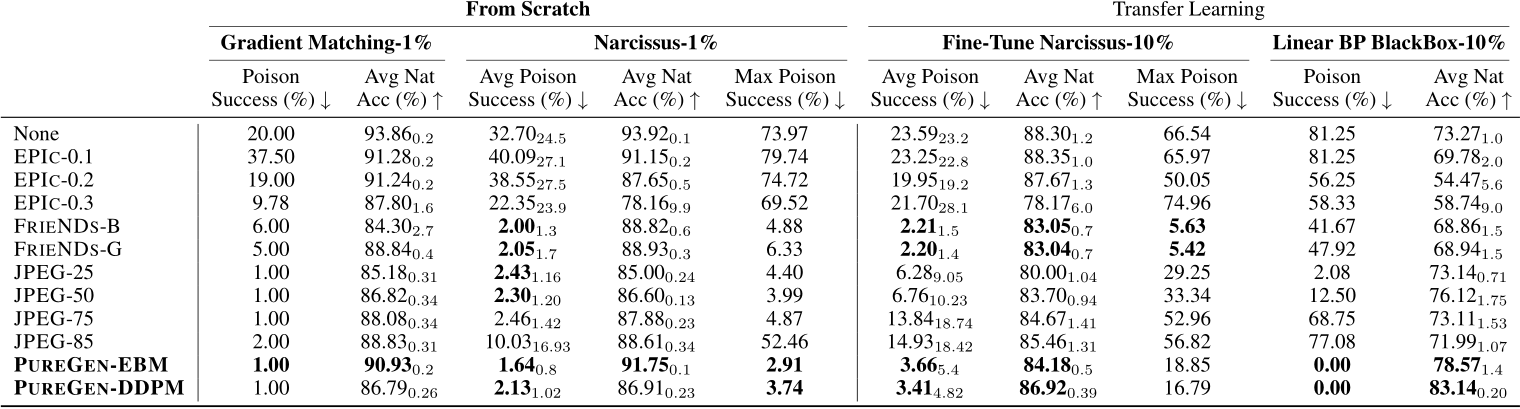

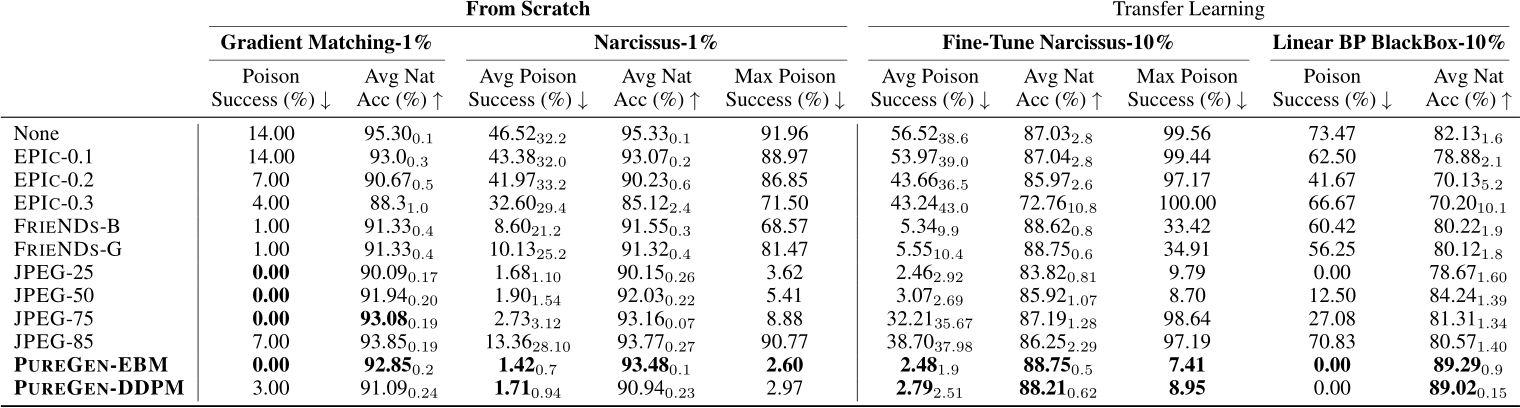

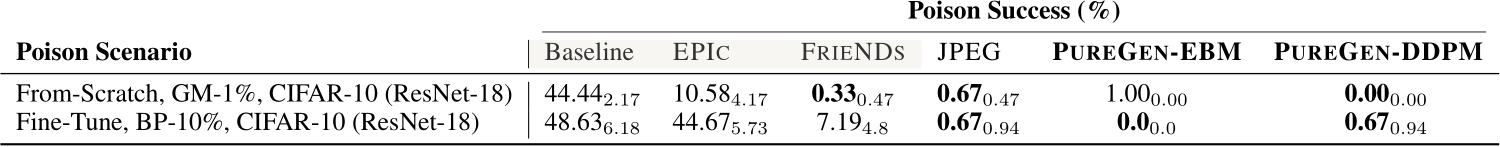

Table 2 shows selected results for additional models MobileNetV2, DenseNet121, and Hyperlight Benchmark (HLB), which is a unique case study with a residual-less network architecture, unique initialization scheme, and super-convergence training method that recently held the world record of achieving 94% test accuracy on CIFAR-10 with just 10 epochs [46]. Due to the fact that PUREGEN is a preprocessing step, it can be readily applied to novel training paradigms with no modifications

Table 2: Results for additional models (MobileNetV2, DenseNet121, and HLB) and the NTGA data-availability attack. PUREGEN remains state-of-the-art for all train-time latent attacks, while NTGA defense shows near SoTA performance. *All NTGA baselines pulled from [30].

unlike previous baselines EPIC and FRIENDS. In all results, PUREGEN is again SoTA, except for NTGA data-availability attack, where PUREGEN is just below SoTA method AVATAR (which is also a diffusion based approach). But we again emphasize data-availability attacks are not the focus of PUREGEN which secures against latent attacks.

The complete results for all models and all versions of each baseline can be found in App. E.

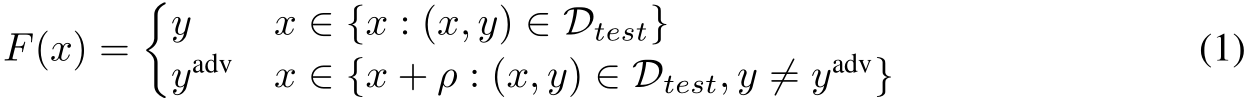

4.3 PUREGEN Robustness to Train Data Shifts, Poisoning, and Defense-Aware Poisons

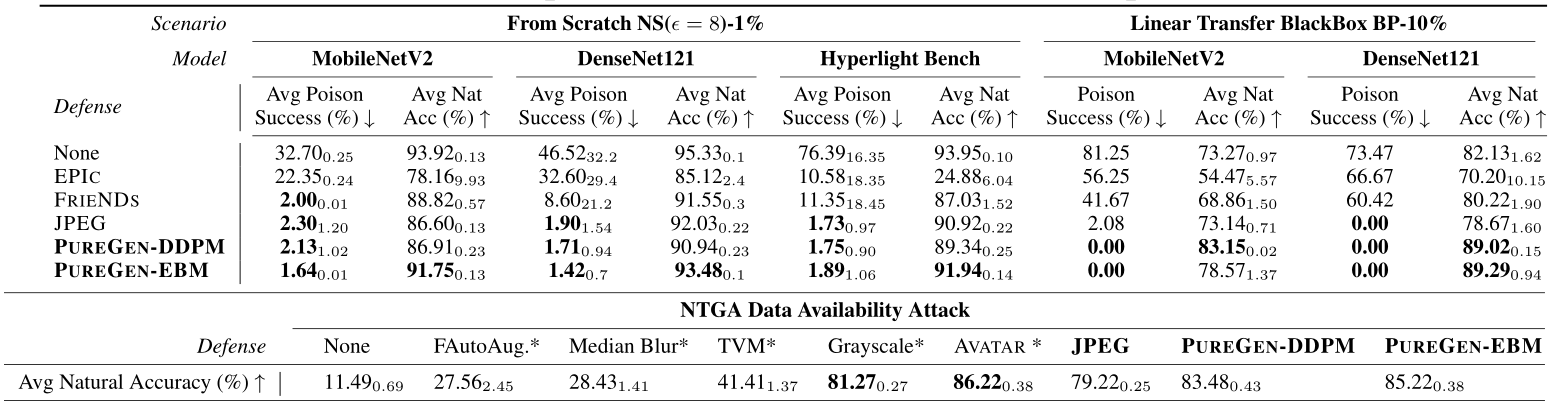

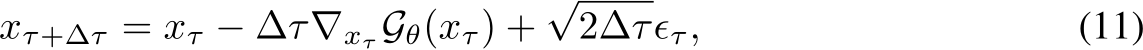

Figure 4: PUREGEN-EBM vs. PUREGEN-DDPM with increasingly Out-of-Distribution training data (for generative model training) and purifying target/attacked distribution CIFAR-10. PUREGEN-EBM is much more robust to distributional shift for natural accuracy while both PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM maintain SoTA poison defense across all train distributions *CIFAR-10 is a “cheating” baseline as clean versions of poisoned images are present in training data.

An important consideration for PUREGEN is the distributional shift between the data used to train the generative models and the target dataset to be purified. Figure 4 explores this by training PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM on increasingly out-of-distribution (OOD) datasets while purifying the CIFAR-10 dataset (NS attack). We quantify the distributional shift using the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) [47] between the original CIFAR-10 training images and the OOD datasets. Notably, both methods maintain SoTA or near SoTA poison defense across all training distributions, highlighting their effectiveness even under distributional shift. The results show that PUREGEN-EBM is more robust to distributional shift in terms of maintaining natural accuracy, with only a slight drop in performance even when trained on highly OOD datasets like Flowers-102 and LFW people. In contrast, PUREGEN-DDPM experiences a more significant drop in natural accuracy as the distributional shift increases. Note that the CIFAR-10 is a “cheating” baseline, as clean versions of the poisoned images are present in the generative model training data, but it provides an upper bound on the performance that can be achieved when the generative models are trained on perfectly in-distribution data.

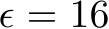

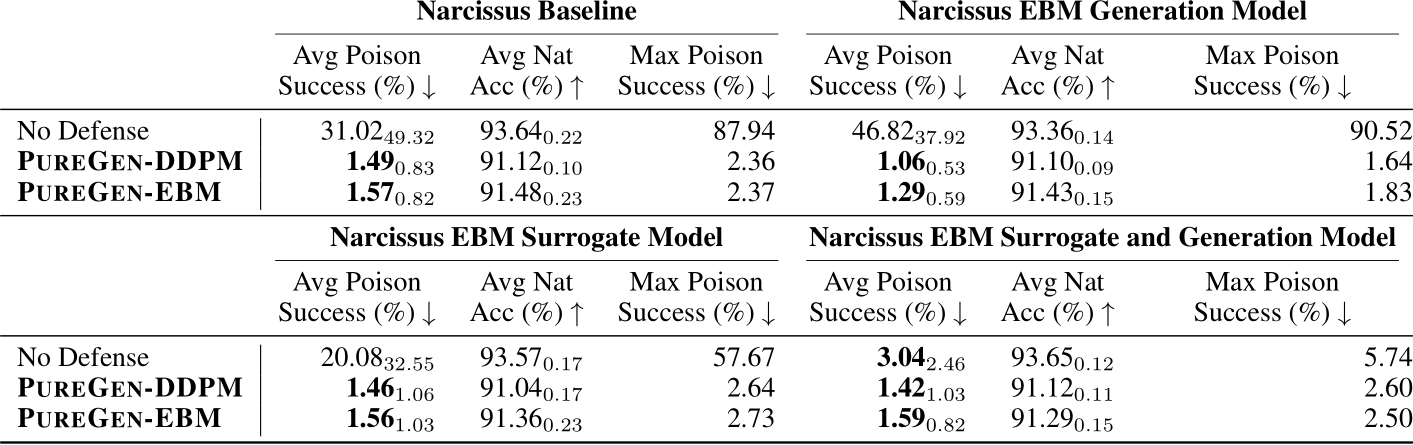

Table 3: Both PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM are robust to NS attack even when fully poisoned (all classes at once) during model training except for NS Eps-16 for PUREGEN-EBM

Another important consideration is the robustness of PUREGEN when the generative models themselves are trained on poisoned data. Table 3 shows the performance of PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM when their training data is fully poisoned with the Narcissus (NS) attack, meaning that all classes are poisoned simultaneously. The results demonstrate that both PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM are highly robust to poisoning during model training, maintaining SoTA poison defense and natural accuracy with only exception being PUREGEN-EBM’s performance on the more challenging NS  attack when poisoned with the same perturbations. While it is unlikely an attacker would have access to both the the generative model and classifier train datasets, these findings highlight the inherent robustness of PUREGEN, as the generative models can effectively learn the underlying clean data distribution even in the presence of poisoned samples during training. This is a key advantage of PUREGEN compared to other defenses, especially when there is no secure dataset.

attack when poisoned with the same perturbations. While it is unlikely an attacker would have access to both the the generative model and classifier train datasets, these findings highlight the inherent robustness of PUREGEN, as the generative models can effectively learn the underlying clean data distribution even in the presence of poisoned samples during training. This is a key advantage of PUREGEN compared to other defenses, especially when there is no secure dataset.

Finally, in App. E.2.1, we show results where we integrate an EBM into the Narcissus crafting pipeline, done by taking a gradient through the EBM MCMC dynamics in three ways based on the specifics of crafting. In all cases, PUREGEN shows almost no defense degradation, and we actually show we can generate more effective poisons over baseline this way. These results further validate the effectiveness of PUREGEN even with defense-aware crafting, which is not a typical assumption in train-time attacks.

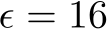

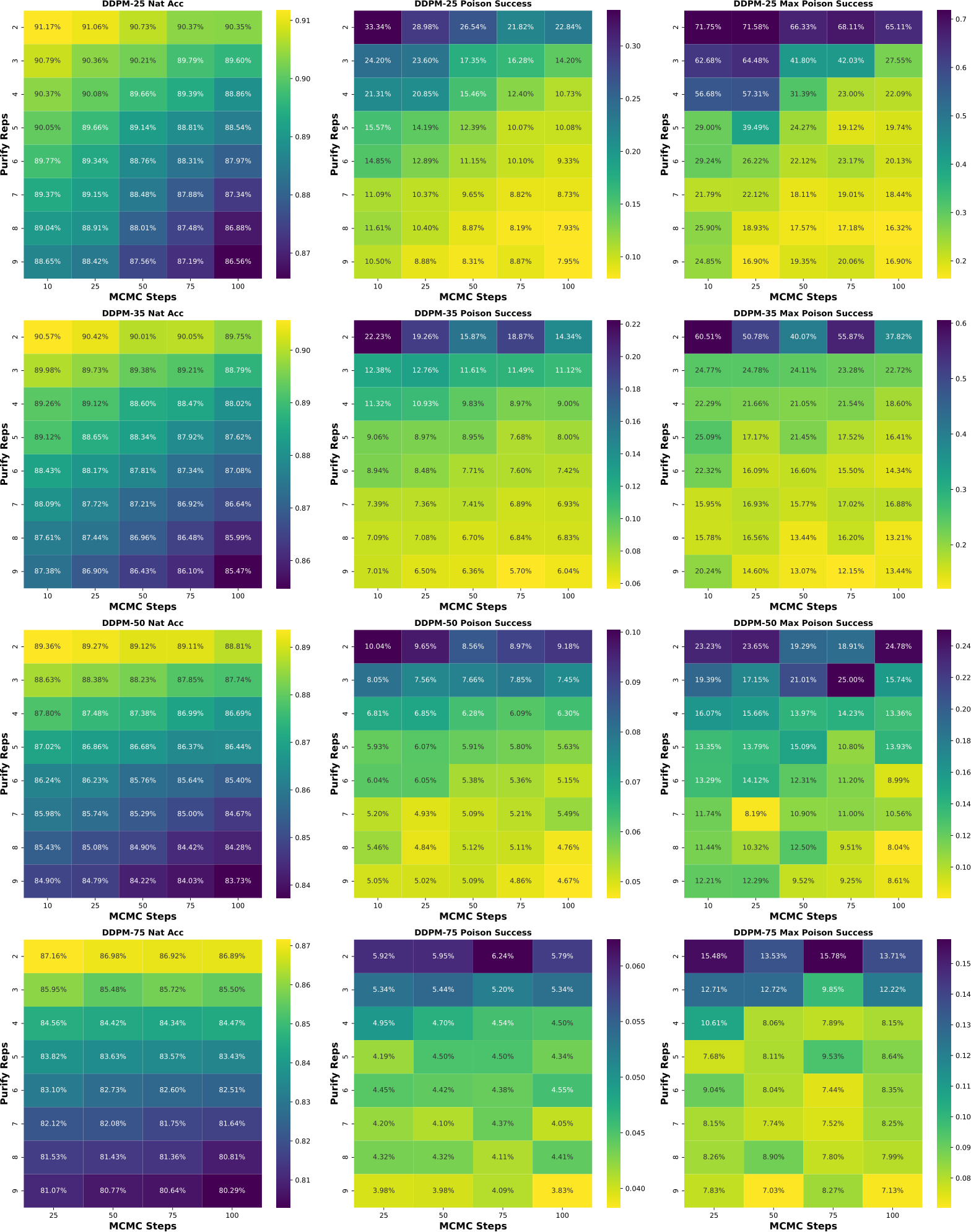

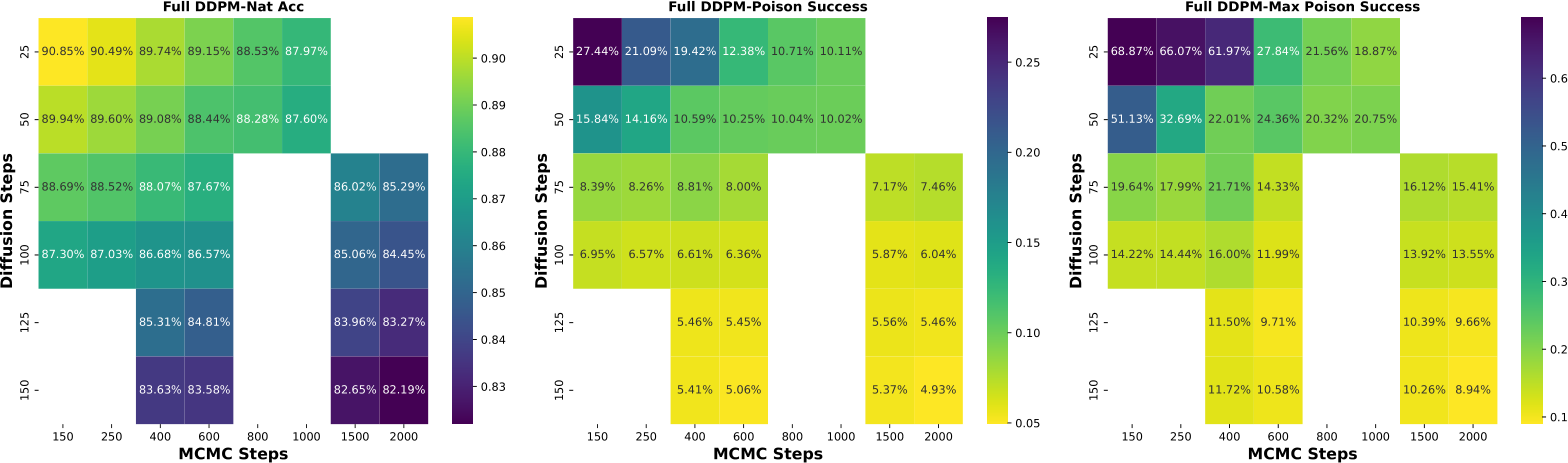

4.4 PUREGEN Extensions on Higher Power Attacks

To leverage the strengths of both PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM, we propose PUREGEN combinations that utilize either both EMB and DPPM back-to-back (PUREGEN-NAIVE), EBM and DDPM with multiple repetitions of smaller steps (PUREGEN-REPS), and finally EBM as a filter to then use EBM/DDPM on only the k highest energy samples as described in 3.3. For additional description, see C, and note that these extensions required extensive hyperparameter search with performance sweeps shown in App F, as there was little intuition for the amount of reps ( ) or the filtering threshold (k) needed. Thus, we do not include these methods in our core results, but we do show the added performance gains on higher power poisons in Table 4, both in terms of increased perturbation size

) or the filtering threshold (k) needed. Thus, we do not include these methods in our core results, but we do show the added performance gains on higher power poisons in Table 4, both in terms of increased perturbation size  and increased poison % (and both together).

and increased poison % (and both together).

Table 4: PUREGEN-NAIVE, PUREGEN-REPS, and PUREGEN-FILT results showing further performance gains on increased poison power scenarios

4.5 PUREGEN Timing and Limitations

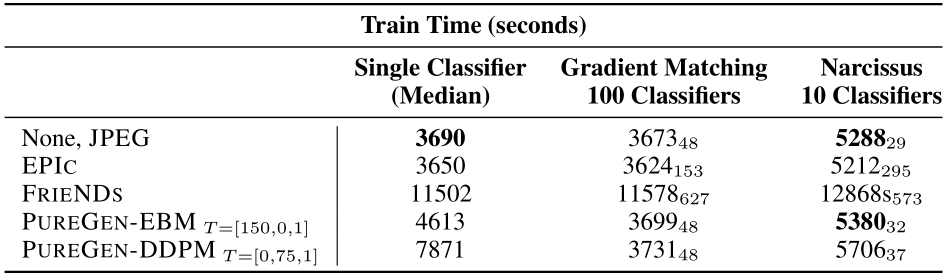

Table 5 presents the training times for using PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM (923 and 4181 seconds respectively to purify) on CIFAR-10 using a TPU V3. Although these times may seem significant, PUREGEN is a universal defense applied once per dataset, making its cost negligible when reused across multiple tasks and poison scenarios. To highlight this, we also present the purification times amortized over the 10 and 100 NS and GM poison scenarios, demonstrating that the cost becomes negligible when the purified dataset is used multiple times relative to baselines like FRIENDS which require retraining for each specific task and poison scenario (while still utilizing the full dataset unlike EPIC). PUREGEN-EBM generally has lower purification times compared to PUREGEN-DDPM, making it more suitable for subtle and rare perturbations. Conversely, PUREGEN-DDPM can handle more severe perturbations but at a higher computational cost and potential reduction in natural accuracy.

Table 5: PUREGEN and baseline Timing Analysis on TPU V3

Training the generative models for PUREGEN involves substantial computational cost and data requirements. However, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 4, these models remain effective even when trained on poisoned or out-of-distribution data. This universal applicability justifies the initial training cost, as the models can defend against diverse poisoning scenarios. So while JPEG is a fairly effective baseline, the added benefits of PUREGEN start to outweigh the compute as the use cases of the dataset increase. While PUREGEN combinations (PUREGEN-REPS and PUREGEN-FILT) show enhanced performance on higher power attacks (Table 4), further research is needed to fully exploit the strengths of both PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM.

5 Conclusion

Poisoning has the potential to become one of the greatest attack vectors to AI models, decreasing model security and eroding public trust. In this work, we introduce PUREGEN, a suite of universal data purification methods that leverage the stochastic dynamics of Energy-Based Models (EBMs) and Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) to defend against train-time data poisoning attacks. PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM effectively purify poisoned datasets by iteratively transforming poisoned samples into the natural data manifold, thus mitigating adversarial perturbations. Our extensive experiments demonstrate that these methods achieve state-of-the-art performance against a range of leading poisoning attacks and can maintain SoTA performance in the face of poisoned or distributionally shifted generative model training data. These versatile and efficient methods set a new standard in protecting machine learning models against evolving data poisoning threats, potentially inspiring greater trust in AI applications.

6 Potential Social Impacts

Poisoning represents one of the greatest emerging threats to AI systems, particularly as foundation models increasingly rely on large, diverse datasets without rigorous quality control against imperceptible perturbations. This vulnerability is especially concerning in high-stakes domains like healthcare, security, and autonomous vehicles, where model integrity is crucial and erroneous outputs could have catastrophic consequences. Our research provides a universal defense method that can be implemented with minimal impact to existing training infrastructure, enabling practitioners to preemptively secure their datasets against state-of-the-art poisoning attacks.

While we acknowledge that the poison defense space can promote an ‘arms race’ of increasingly sophisticated attacks and defenses, our approach’s universality poses a fundamentally harder challenge for attackers, even when using defense-aware crafting E.2.1. We specifically focus on defending against latent backdoor vulnerabilities rather than data availability attacks, as the latter can serve legitimate purposes in protecting content creators’ rights. By providing robust defense against malicious poisoning while preserving natural model performance, our method helps build trust in AI systems for increasingly consequential real-world applications.

7 Acknowledgments

This work is supported with Cloud TPUs from Google’s Tensorflow Research Cloud (TFRC). We would like to acknowledge Jonathan Mitchell, Mitch Hill, Yuan Du and Kathrine Abreu for support and discussion on base EBM and Diffusion code, and Yunzheng Zhu for his help in crafting poisons.

References

[1] T. Gu, B. Dolan-Gavitt, and S. Garg, “Badnets: Identifying vulnerabilities in the machine learning model supply chain,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.06733, 2017.

[2] A. Turner, D. Tsipras, and A. Madry, “Clean-label backdoor attacks,” 2018.

[3] H. Souri, M. Goldblum, L. Fowl, R. Chellappa, and T. Goldstein, “Sleeper agent: Scalable hidden trigger backdoors for neural networks trained from scratch,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.08970, 2021.

[4] Y. Zeng, M. Pan, H. A. Just, L. Lyu, M. Qiu, and R. Jia, “Narcissus: A practical clean-label backdoor attack with limited information,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.05255, 2022.

[5] A. Shafahi, W. R. Huang, M. Najibi, O. Suciu, C. Studer, T. Dumitras, and T. Goldstein, “Poison frogs! targeted clean-label poisoning attacks on neural networks,” 2018.

[6] C. Zhu, W. R. Huang, H. Li, G. Taylor, C. Studer, and T. Goldstein, “Transferable clean-label poisoning attacks on deep neural nets,” in International Conference on Machine Learning, 2019, pp. 7614–7623.

[7] W. R. Huang, J. Geiping, L. Fowl, G. Taylor, and T. Goldstein, “Metapoison: Practical generalpurpose clean-label data poisoning,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 2020.

[8] J. Geiping, L. H. Fowl, W. R. Huang, W. Czaja, G. Taylor, M. Moeller, and T. Goldstein, “Witches’ brew: Industrial scale data poisoning via gradient matching,” in International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://openreview.net/forum?id=01olnfLIbD

[9] H. Aghakhani, D. Meng, Y.-X. Wang, C. Kruegel, and G. Vigna, “Bullseye polytope: A scalable clean-label poisoning attack with improved transferability,” in 2021 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P). IEEE, 2021, pp. 159–178.

[10] J. Feng, Q.-Z. Cai, and Z.-H. Zhou, “Learning to confuse: Generating training time adversarial data with auto-encoder,” 2019.

[11] H. Huang, X. Ma, S. M. Erfani, J. Bailey, and Y. Wang, “Unlearnable examples: Making personal data unexploitable,” 2021.

[12] C.-H. Yuan and S.-H. Wu, “Neural tangent generalization attacks,” in Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, ser. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, M. Meila and T. Zhang, Eds., vol. 139. PMLR, 18–24 Jul 2021, pp. 12 230–12 240. [Online]. Available: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v139/yuan21b.html

[13] G. F. Cretu, A. Stavrou, M. E. Locasto, S. J. Stolfo, and A. D. Keromytis, “Casting out demons: Sanitizing training data for anomaly sensors,” in 2008 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (sp 2008). IEEE, 2008, pp. 81–95.

[14] J. Steinhardt, P. W. Koh, and P. Liang, “Certified defenses for data poisoning attacks,” 2017.

[15] B. Tran, J. Li, and A. Madry, “Spectral signatures in backdoor attacks,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018, pp. 8000–8010.

[16] B. Chen, W. Carvalho, N. Baracaldo, H. Ludwig, B. Edwards, T. Lee, I. Molloy, and B. Srivastava, “Detecting backdoor attacks on deep neural networks by activation clustering,” in SafeAI@ AAAI, 2019.

[17] N. Peri, N. Gupta, W. R. Huang, L. Fowl, C. Zhu, S. Feizi, T. Goldstein, and J. P. Dickerson, “Deep k-nn defense against clean-label data poisoning attacks,” in European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2020, pp. 55–70.

[18] Y. Yang, T. Y. Liu, and B. Mirzasoleiman, “Not all poisons are created equal: Robust training against data poisoning,” 2022.

[19] O. Pooladzandi, D. Davini, and B. Mirzasoleiman, “Adaptive second order coresets for dataefficient machine learning,” 2022.

[20] M. Weber, X. Xu, B. Karlaš, C. Zhang, and B. Li, “Rab: Provable robustness against backdoor attacks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.08904, 2020.

[21] A. Levine and S. Feizi, “Deep partition aggregation: Provable defenses against general poisoning attacks,” in International Conference on Learning Representations, 2020.

[22] M. Abadi, A. Chu, I. Goodfellow, H. B. McMahan, I. Mironov, K. Talwar, and L. Zhang, “Deep learning with differential privacy,” in Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 2016, pp. 308–318.

[23] Y. Ma, X. Z. Zhu, and J. Hsu, “Data poisoning against differentially-private learners: Attacks and defenses,” in International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2019.

[24] Y. Li, X. Lyu, N. Koren, L. Lyu, B. Li, and X. Ma, “Anti-backdoor learning: Training clean models on poisoned data,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 34, 2021.

[25] L. Tao, L. Feng, J. Yi, S.-J. Huang, and S. Chen, “Better safe than sorry: Preventing delusive adversaries with adversarial training,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 34, 2021.

[26] T. Y. Liu, Y. Yang, and B. Mirzasoleiman, “Friendly noise against adversarial noise: A powerful defense against data poisoning attacks,” 2023.

[27] J. Geiping, L. Fowl, G. Somepalli, M. Goldblum, M. Moeller, and T. Goldstein, “What doesn’t kill you makes you robust (er): Adversarial training against poisons and backdoors,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.13624, 2021.

[28] A. Madry, A. Makelov, L. Schmidt, D. Tsipras, and A. Vladu, “Towards deep learning models resistant to adversarial attacks,” in International Conference on Learning Representations, 2018.

[29] M. Hill, J. C. Mitchell, and S.-C. Zhu, “Stochastic security: Adversarial defense using long-run dynamics of energy-based models,” in International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://openreview.net/forum?id=gwFTuzxJW0

[30] H. M. Dolatabadi, S. Erfani, and C. Leckie, “The devil’s advocate: Shattering the illusion of unexploitable data using diffusion models,” 2024.

[31] W. Nie, B. Guo, Y. Huang, C. Xiao, A. Vahdat, and A. Anandkumar, “Diffusion models for adversarial purification,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.07460, 2022.

[32] X. Chen, C. Liu, B. Li, K. Lu, and D. Song, “Targeted backdoor attacks on deep learning systems using data poisoning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.05526, 2017.

[33] Y. Liu, S. Ma, Y. Aafer, W.-C. Lee, J. Zhai, W. Wang, and X. Zhang, “Trojaning attack on neural networks,” 2017.

[34] A. Saha, A. Subramanya, and H. Pirsiavash, “Hidden trigger backdoor attacks,” 2019.

[35] D. Yu, H. Zhang, W. Chen, J. Yin, and T.-Y. Liu, “Availability attacks create shortcuts,” in Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, ser. KDD ’22. ACM, Aug. 2022. [Online]. Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/3534678.3539241

[36] E. Borgnia, V. Cherepanova, L. Fowl, A. Ghiasi, J. Geiping, M. Goldblum, T. Goldstein, and A. Gupta, “Strong data augmentation sanitizes poisoning and backdoor attacks without an accuracy tradeoff,” in ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2021, pp. 3855–3859.

[37] S. Hong, V. Chandrasekaran, Y. Kaya, T. Dumitra¸s, and N. Papernot, “On the effectiveness of mitigating data poisoning attacks with gradient shaping,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.11497, 2020.

[38] B. Jayaraman and D. Evans, “Evaluating differentially private machine learning in practice,” in 28th {USENIX} Security Symposium ({USENIX} Security 19), 2019, pp. 1895–1912.

[39] D. Madaan, J. Shin, and S. J. Hwang, “Learning to generate noise for multi-attack robustness,” 2021.

[40] N. Das, M. Shanbhogue, S.-T. Chen, F. Hohman, S. Li, L. Chen, M. E. Kounavis, and D. H. Chau, “Shield: Fast, practical defense and vaccination for deep learning using jpeg compression,” 2018.

[41] J. Xie, Y. Lu, S.-C. Zhu, and Y. Wu, “A theory of generative convnet,” in Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning, 2016, pp. 2635–2644.

[42] J. Ho, A. Jain, and P. Abbeel, “Denoising diffusion probabilistic models,” 2020.

[43] A. Krizhevsky, V. Nair, and G. Hinton, “Cifar-10 (canadian institute for advanced research).” [Online]. Available: http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html

[44] L. N. Darlow, E. J. Crowley, A. Antoniou, and A. J. Storkey, “Cinic-10 is not imagenet or cifar-10,” 2018.

[45] G. Griffin, A. Holub, and P. Perona, “Caltech 256,” Apr 2022.

[46] T. Balsam, “hlb-cifar10,” 2023, released on 2023-02-12. [Online]. Available: https: //github.com/tysam-code/hlb-CIFAR10

[47] M. Heusel, H. Ramsauer, T. Unterthiner, B. Nessler, and S. Hochreiter, “Gans trained by a two time-scale update rule converge to a local nash equilibrium,” 2018.

[48] E. Nijkamp, M. Hill, T. Han, S.-C. Zhu, and Y. N. Wu, “On the anatomy of MCMC-based maximum likelihood learning of energy-based models,” in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 34, 2020.

[49] T. Miyato, T. Kataoka, M. Koyama, and Y. Yoshida, “Spectral normalization for generative adversarial networks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.05957, 2018.

[50] A. Schwarzschild, M. Goldblum, A. Gupta, J. P. Dickerson, and T. Goldstein, “Just how toxic is data poisoning? a unified benchmark for backdoor and data poisoning attacks,” 2021.

[51] J. Whitaker, “Hugging face ddpm butterflies model,” https://huggingface.co/johnowhitaker/ ddpm-butterflies-32px, accessed: 2024-08-05.

[52] N. Onzo, “Hugging face ddpm anime model,” https://huggingface.co/onragi/ anime-ddpm-32-res2-v3, accessed: 2024-08-05.

[53] N. Kokhlikyan, V. Miglani, M. Martin, E. Wang, B. Alsallakh, J. Reynolds, A. Melnikov, N. Kliushkina, C. Araya, S. Yan, and O. Reblitz-Richardson, “Captum: A unified and generic model interpretability library for pytorch,” 2020.

A Further Background

A.1 Poisons

The goal of adding train-time poisons is to change the prediction of a set of target examples

or triggered examples

or triggered examples  to an adversarial label

to an adversarial label

Targeted clean-label data poisoning attacks can be formulated as the following bi-level optimization problem:

For a triggerless poison, we solve for the ideal perturbations  to minimize the adversarial loss on the target images, where

to minimize the adversarial loss on the target images, where  . To address the above optimization problem, powerful poisoning attacks such as Meta Poison (MP) [7], Gradient Matching (GM) [8], and Bullseye Polytope (BP) [9] craft the poisons to mimic the gradient of the adversarially labeled target, i.e.,

. To address the above optimization problem, powerful poisoning attacks such as Meta Poison (MP) [7], Gradient Matching (GM) [8], and Bullseye Polytope (BP) [9] craft the poisons to mimic the gradient of the adversarially labeled target, i.e.,

Minimizing the training loss on RHS of Equation 7 also minimizes the adversarial loss objective of Equation 6.

For the triggered poison, Narcissus (NS), we find the most representative patch  for class

for class  given C, defining Equation 6 with

given C, defining Equation 6 with  , and

, and

. In particular, this patch uses a public out-of-distribution dataset

. In particular, this patch uses a public out-of-distribution dataset  and only the targeted class

and only the targeted class  . As finding this patch comes from another natural dataset and does not depend on other train classes, NS has been more flexible to model architecture, dataset, and training regime [4].

. As finding this patch comes from another natural dataset and does not depend on other train classes, NS has been more flexible to model architecture, dataset, and training regime [4].

Background for data availability attacks can be found in [35]. The goal for data availability attacks (sometimes referred to as “unlearnable” attacks is to collapse the test accuracy, and hence the model’s ability to generalize, or learn useful representations, from the train dataset. As we discuss in the main paper, such attacks are immediately obvious when training a model, or rather create a region of poor performance in the model. These attacks do not create latent vulnerabilities that can then be exploited by an adversary. Thus we do not focus on, or investigate our methods with any detail for availability attacks. Further, we discuss in the Societal Impacts section how such attacks have many ethical uses for privacy and data protection 6.

A.2 Further EBM Discussions

Recalling the Gibbs-Boltzmann density from Equation 3,

where  denotes an image signal, and q(x) is a reference measure, often a uniform or standard normal distribution. Here,

denotes an image signal, and q(x) is a reference measure, often a uniform or standard normal distribution. Here,  signifies the energy potential, parameterized by a ConvNet with parameters

signifies the energy potential, parameterized by a ConvNet with parameters

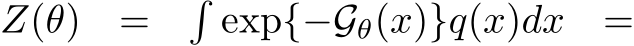

The normalizing constant, or the partition function,

![Eq[exp(−Gθ(x))]](https://cdn.bytez.com/mobilePapers/v2/neurips/94623/images/13-20.png) , while essential, is generally analytically intractable. In practice,

, while essential, is generally analytically intractable. In practice,  is not computed explicitly, as

is not computed explicitly, as  sufficiently informs the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling process.

sufficiently informs the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling process.

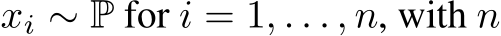

As which  of the images are poisoned is unknown, we treat them all the same for a universal defense. Considering i.i.d. samples

of the images are poisoned is unknown, we treat them all the same for a universal defense. Considering i.i.d. samples  sufficiently large, the sample average over

sufficiently large, the sample average over  converges to the expectation under P and one can learn a parameter

converges to the expectation under P and one can learn a parameter  such that

such that  . For notational simplicity, we equate the sample average with the expectation.

. For notational simplicity, we equate the sample average with the expectation.

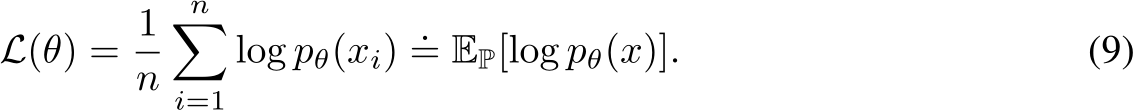

The objective is to minimize the expected negative log-likelihood, formulated as:

The derivative of this log-likelihood, crucial for parameter updates, is given by:

where solving for the critical points results in the average gradient of a batch of real images ( ) should be equal to the average gradient of a synthesized batch of examples from the real images

) should be equal to the average gradient of a synthesized batch of examples from the real images  . The parameters are then updated as

. The parameters are then updated as  , where

, where  is the learning rate.

is the learning rate.

In this work, to obtain the synthesized samples  from the current distribution

from the current distribution  we use the iterative application of the Langevin update as the Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) method, first introduced in Equation 4:

we use the iterative application of the Langevin update as the Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) method, first introduced in Equation 4:

where  indexes the time step of the Langevin dynamics, and

indexes the time step of the Langevin dynamics, and  is the discretization of time [41].

is the discretization of time [41].  can be obtained by back-propagation. If the gradient term dominates the diffusion noise term, the Langevin dynamics behave like gradient descent. We implement EBM training following [48], see App. A.2.1 for details.

can be obtained by back-propagation. If the gradient term dominates the diffusion noise term, the Langevin dynamics behave like gradient descent. We implement EBM training following [48], see App. A.2.1 for details.

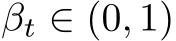

A.2.1 EBM Training

Algorithm 2 is pseudo-code for the training procedure of a data-initialized convergent EBM. We use the generator architecture of the SNGAN [49] for our EBM as our network architecture. Further intuiton can be found in App. B.1.

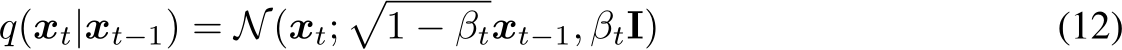

A.3 DDPM Background

The forward process successively adds noise over a sequence of time steps, eventually resulting in values that follow a prior distribution, typically a standard Gaussian as in:

where  be a clean image sampled from the data distribution. The forward process is defined by a fixed Markov chain with Gaussian transitions for a sequence of timesteps t = 1, . . . , T:

be a clean image sampled from the data distribution. The forward process is defined by a fixed Markov chain with Gaussian transitions for a sequence of timesteps t = 1, . . . , T:

The reverse process is defined as the conditional distribution of the previous variable at a timestep, given the current one:

where  is a variance schedule. After

is a variance schedule. After  is nearly an isotropic Gaussian distribution. This reverse process is parameterized by a neural network and trained to de-noise a variable from the prior to match the real data distribution. Generating from a standard DDPM involves drawing samples from the prior, and then running the learned de-noising process to gradually remove noise and yield a final sample.

is nearly an isotropic Gaussian distribution. This reverse process is parameterized by a neural network and trained to de-noise a variable from the prior to match the real data distribution. Generating from a standard DDPM involves drawing samples from the prior, and then running the learned de-noising process to gradually remove noise and yield a final sample.

B PUREGEN Further Intuition

B.1 Why EBM Langevin Dynamics Purify

The theoretical basis for eliminating adversarial signals using MCMC sampling is rooted in the established steady-state convergence characteristic of Markov chains. The Langevin update, as specified in Equation (4), converges to the distribution  learned from unlabeled data after an infinite number of Langevin steps. The memoryless nature of a steady-state sampler guarantees that after enough steps, all adversarial signals will be removed from an input sample image. Full mixing between the modes of an EBM will undermine the original natural image class features, making classification impossible [29]. Nijkamp et al. [2020] reveals that without proper tuning, EBM learning heavily gravitates towards non-convergent ML where short-run MCMC samples have a realistic appearance and long-run MCMC samples have unrealistic ones. In this work, we use image initialized convergent learning.

learned from unlabeled data after an infinite number of Langevin steps. The memoryless nature of a steady-state sampler guarantees that after enough steps, all adversarial signals will be removed from an input sample image. Full mixing between the modes of an EBM will undermine the original natural image class features, making classification impossible [29]. Nijkamp et al. [2020] reveals that without proper tuning, EBM learning heavily gravitates towards non-convergent ML where short-run MCMC samples have a realistic appearance and long-run MCMC samples have unrealistic ones. In this work, we use image initialized convergent learning.  is described further by Algorithm 1[48].

is described further by Algorithm 1[48].

The metastable nature of EBM models exhibits characteristics that permit the removal of adversarial signals while maintaining the natural image’s class and appearance [29]. Metastability guarantees that over a short number of steps, the EBM will sample in a local mode, before mixing between modes. Thus, it will sample from the initial class and not bring class features from other classes in its learned distribution. Consider, for instance, an image of a horse that has been subjected to an adversarial  perturbation, intended to deceive a classifier into misidentifying it as a dog. The perturbation, constrained by the

perturbation, intended to deceive a classifier into misidentifying it as a dog. The perturbation, constrained by the  -norm ball, is insufficient to shift the EBM’s recognition of the image away from the horse category. Consequently, during the brief sampling process, the EBM actively replaces the adversarially induced ‘dog’ features with characteristics more typical of horses, as per its learned distribution resulting in an output image resembling a horse more closely than a dog. It is important to note, however, that while the output image aligns more closely with the general characteristics of a horse, it does not precisely replicate the specific horse from the original, unperturbed image.

-norm ball, is insufficient to shift the EBM’s recognition of the image away from the horse category. Consequently, during the brief sampling process, the EBM actively replaces the adversarially induced ‘dog’ features with characteristics more typical of horses, as per its learned distribution resulting in an output image resembling a horse more closely than a dog. It is important to note, however, that while the output image aligns more closely with the general characteristics of a horse, it does not precisely replicate the specific horse from the original, unperturbed image.

We use mid-run chains for our EBM defense to remove adversarial signals while maintaining image features needed for accurate classification. The steady-state convergence property ensures adversarial signals will eventually vanish, while metastable behaviors preserve features of the initial state. We can see PUREGEN-EBM sample purification examples in Fig. 5 below and how clean and poisoned sampled converge and poison perturbations are removed in the mid-run region (100-2000 steps for us).

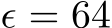

Figure 5: PUREGEN-EBM purification with various MCMC steps

Our experiments show that the mid-run trajectories (100-1000 MCMC steps) we use to preprocess the dataset X capitalize on these metastable properties by effectively purifying poisons while retaining high natural accuracy on  with no training modification needed. Intuitively, one can think of the MCMC process as a directed random walk toward a low-energy, more probable natural image version of the original image. The mid-range dynamics stay close to the original image, but in a lower energy manifold which removes the majority of poisoned perturbations.

with no training modification needed. Intuitively, one can think of the MCMC process as a directed random walk toward a low-energy, more probable natural image version of the original image. The mid-range dynamics stay close to the original image, but in a lower energy manifold which removes the majority of poisoned perturbations.

B.2 PUREGEN Additional L2 Dynamics Images

Additional L2 Dynamics specifically for Narcissus  are shown in Figures 6 and 7.

are shown in Figures 6 and 7.

Figure 6: L2 Dynamics for Narcissus

Figure 7: Energy distributions with Narcissus

C PUREGEN Extensions on Higher Power Attacks

We continue with the notation introduced in 3.3, where  is the random variable of a fixed image x, and we define

is the random variable of a fixed image x, and we define  represents the number of EBM MCMC steps,

represents the number of EBM MCMC steps,  represents the number of diffusion steps, and

represents the number of diffusion steps, and  represents the number of times these steps are repeated.

represents the number of times these steps are repeated.

To incorporate EBM filtering, we order D by  and partition the ordering based on k into

and partition the ordering based on k into  , where

, where  contains k|D| datapoints with the maximal energy (where k = 1 results in purifying everything and k = 0 is traditional training). Then, with some abuse of notation,

contains k|D| datapoints with the maximal energy (where k = 1 results in purifying everything and k = 0 is traditional training). Then, with some abuse of notation,

To leverage the strengths of both PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM, we propose PUREGEN combinations:

| 1. PUREGEN-NAIVE (): Apply a fixed number of PUREGEN-EBM steps followed by PUREGEN-DDPM steps. While this approach does improve the purification results compared to using either method alone, it does not fully exploit the synergy between the two techniques. |

| 2. PUREGEN-REPS (): To better leverage the strengths of both methods, we propose a repetitive combination, where we alternate between a smaller number of PUREGEN-EBM and PUREGEN-DDPM steps for multiple iterations. |

| 3. PUREGEN-FILT (): In this combination, we first use PUREGEN-EBM to identify a percentage of the highest energy points in the dataset, which are more likely to be samples with poisoned perturbations as shown in Fig. 1. We then selectively apply PUREGEN-EBM or PUREGEN-DDPM purification to these high-energy points. |

We note that methods 2 and 3 require extensive hyperparameter search with performance sweeps using the HLB model in App F, as there was little intuition for the amount of reps ( ) or the filtering threshold (k) needed. Thus, we do not include these methods in our core results, but instead show the added performance gains on higher power poisons in Table 4, both in terms of increased perturbation size

) or the filtering threshold (k) needed. Thus, we do not include these methods in our core results, but instead show the added performance gains on higher power poisons in Table 4, both in terms of increased perturbation size  and increased poison % (and both together). We note that 10% would mean the adversary has poisoned the entire class in CIFAR-10 with an NS trigger, and

and increased poison % (and both together). We note that 10% would mean the adversary has poisoned the entire class in CIFAR-10 with an NS trigger, and  is starting to approach visible perturbations, but both are still highly challenging scenarios worth considering for purification.

is starting to approach visible perturbations, but both are still highly challenging scenarios worth considering for purification.

D Poison Sourcing and Experiment Implementation Details

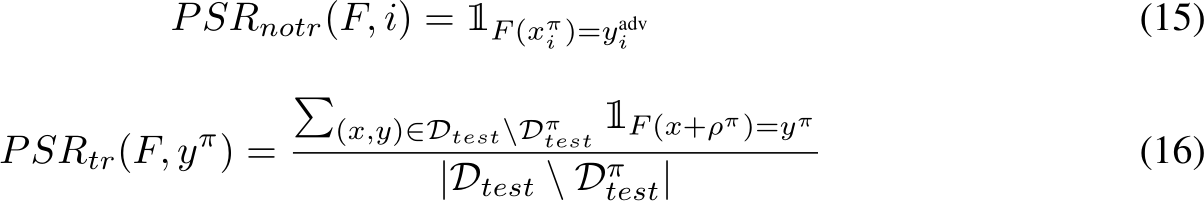

Triggerless attacks GM and BP poison success refers to the number of single-image targets successfully flipped to a target class (with 50 or 100 target image scenarios) while the natural accuracy is averaged across all target image training runs. Triggered attack Narcissus poison success is measured as the number of non-class samples from the test dataset shifted to the trigger class when the trigger is applied, averaged across all 10 classes, while the natural accuracy is averaged across the 10 classes on the un-triggered test data. We include the worst-defended class poison success. The Poison Success Rate for a single experiment can be defined for triggerless  and triggered

and triggered  poisons as:

poisons as:

Note that all results except for Poison Success Rate for GM and BP attacks have a standard deviation, since those attacks are based on a single image class flip for a single classifiers training run. We do provide a subset with results for a single poison paradigm of BP and GM in App. E.2.3 where we used 3 different seeds for the training 3 classifiers for each of the 50 and 100 runs respectively to get a standard deviation, showing these results are low variance relative to the difference in results between baselines and our method. The compute required to collect such results across all scenarios would be extensive. .

D.1 Poison Sourcing

D.1.1 Bullseye Polytope

The Bullseye Polytope (BP) poisons are sourced from two distinct sets of authors. From the original authors of BP [9], we obtain poisons crafted specifically for a black-box scenario targeting ResNet18 and DenseNet121 architectures, and grey-box scenario for MobileNet (used in poison crafting). These poisons vary in the percentage of data poisoned, spanning 1%, 2%, 5% and 10% for the linear-transfer mode and a single 1% fine-tune mode for all models over a 500 image transfer dataset. Each of these scenarios has 50 datasets that specify a single target sample in the test-data. We also use a benchmark paper that provides a pre-trained white-box scenario on CIFAR-100 [50]. This dataset includes 100 target samples with strong poison success, but the undefended natural accuracy baseline is much lower.

D.1.2 Gradient Matching

For GM, we use 100 publicly available datasets provided by [8]. Each dataset specifies a single target image corresponding to 500 poisoned images in a target class. The goal of GM is for the poisons to move the target image into the target class, without changing too much of the remaining test dataset using gradient alignment. Therefore, each individual dataset training gives us a single datapoint of whether the target was correctly moved into the poisoned target class and the attack success rate is across all 100 datasets provided.

D.1.3 Narcissus

For Narcissus triggered attack, we use the same generating process as described in the Narcissus paper, we apply the poison with a slight change to more closely match with the baseline provided by [50]. We learn a patch with  on the entire 32-by-32 size of the image, per class, using the Narcissus generation method. We keep the number of poisoned samples comparable to GM for from-scratch experiment, where we apply the patch to 500 images (1% of the dataset) and test on the patched dataset without the multiplier. In the fine-tune scenarios, we vary the poison% over 1%, 2.5%, and 10%, by modifying either the number of poisoned images or the transfer dataset size (specifically 20/2000, 50/2000, 50/500 poison/train samples).

on the entire 32-by-32 size of the image, per class, using the Narcissus generation method. We keep the number of poisoned samples comparable to GM for from-scratch experiment, where we apply the patch to 500 images (1% of the dataset) and test on the patched dataset without the multiplier. In the fine-tune scenarios, we vary the poison% over 1%, 2.5%, and 10%, by modifying either the number of poisoned images or the transfer dataset size (specifically 20/2000, 50/2000, 50/500 poison/train samples).

D.1.4 Neural Tangent Availability Attacks

For Neural Tangent Availability Attack, the full NTGA dataset (all samples poisoned) is sourced from the authors of the original NTGA attack paper [12]. Baseline defenses are pull from AVATAR [30].

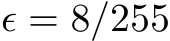

D.2 Training Parameters

We follow the training hyperparameters given by [18, 4, 9, 50] for GM, NS, BP Black/Gray-Box, and BP White-Box respectively as closely as we can, with moderate modifications to align poison scenarios. HyperlightBench training followed the original creators settings and we only substituted in a poisoned dataloader [46].

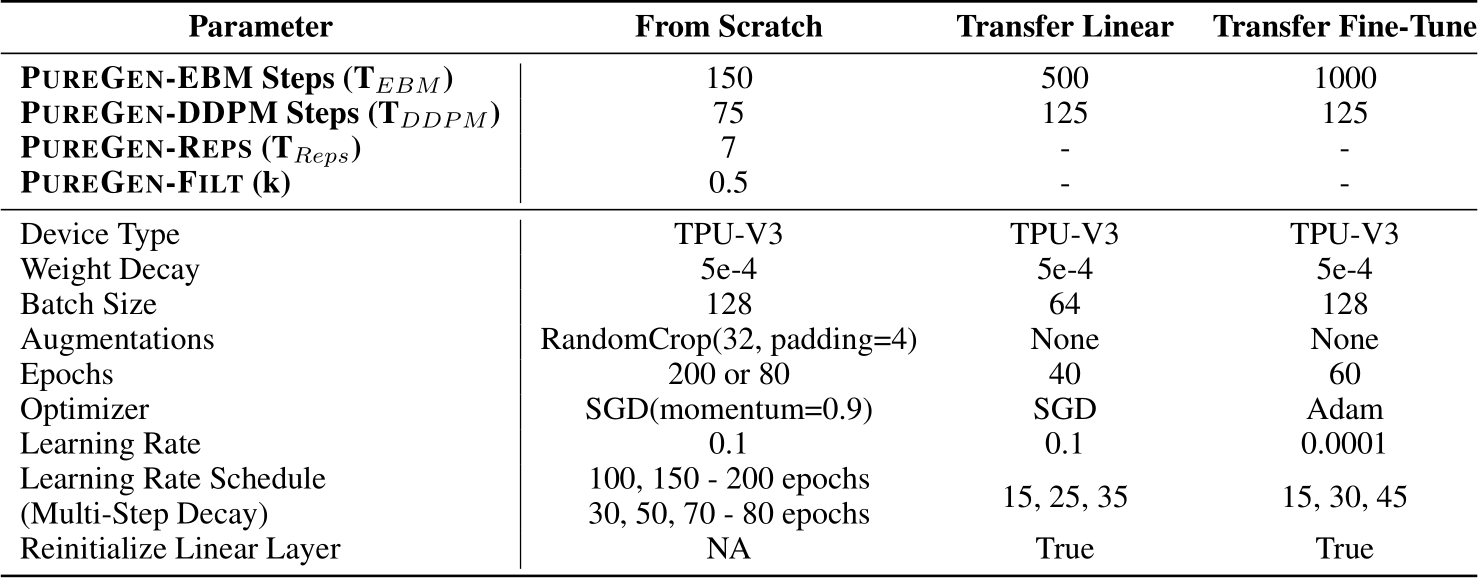

D.3 Core Results Compute

Training compute for core result only which is in Table 1 on a TPU V3.

E Additional Results

E.1 Extended Core Results

E.1.1 Full Results Primary Experiments

Results on all primary poison scenarios with ResNet18 classifier including all EPIC versions (various subset sizes and selection frequency), FRIENDS versions (bernouilli or gaussian added noise trasnform), and all natural JPEG versions (compression ratios). Green highlight indicates a baseline defense that was selected for the main paper results table chosen by the best poison defense performance that did not result in significant natural accuracy degradaion. For both TinyImageNet and CINIC-10 from-scratch results, best performing baseline settings were used from respective poison scenarios in CIFAR-10 for compute reasons (so there are no additonal results and hence they are removed from this table).

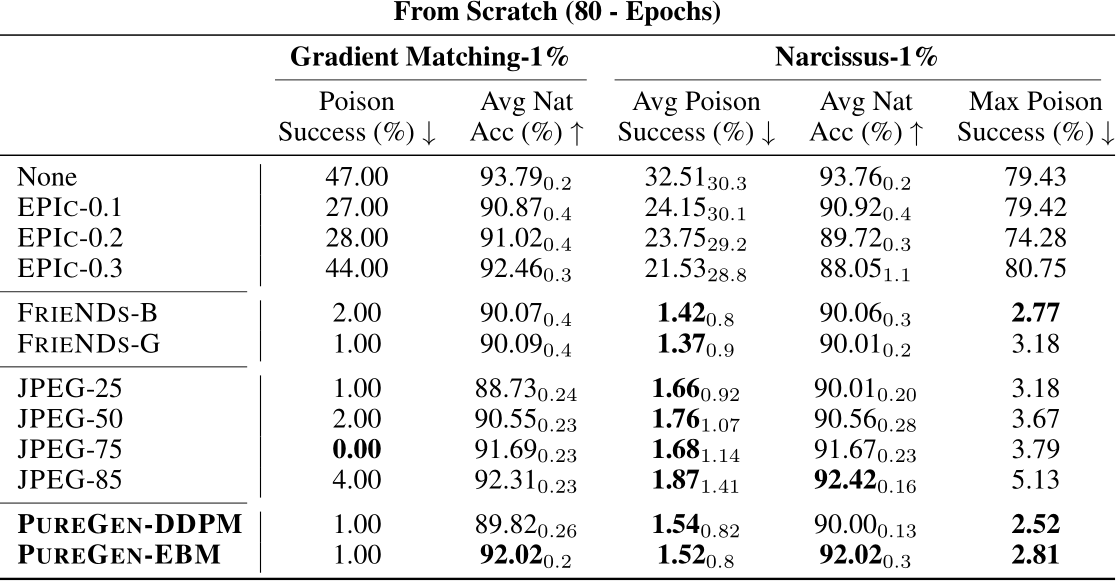

E.1.2 From Scratch 80 Epochs Experiments

Baseline FRIENDS [26] includes an 80-epoch from-scratch scenario to show poison defense on a faster training schedule. None of these results are included in the main paper, but we show again SoTA or near SoTA for PUREGEN against all baselines (and JPEG is again introduced as a baseline).

Table 7: From-Scratch 80-Epochs Results (ResNet-18, CIFAR-10)

E.1.3 Full Results for MobileNetV2 and DenseNet121

Table 8: MobileNetV2 Full Results

Table 9: DenseNet121 Full Results

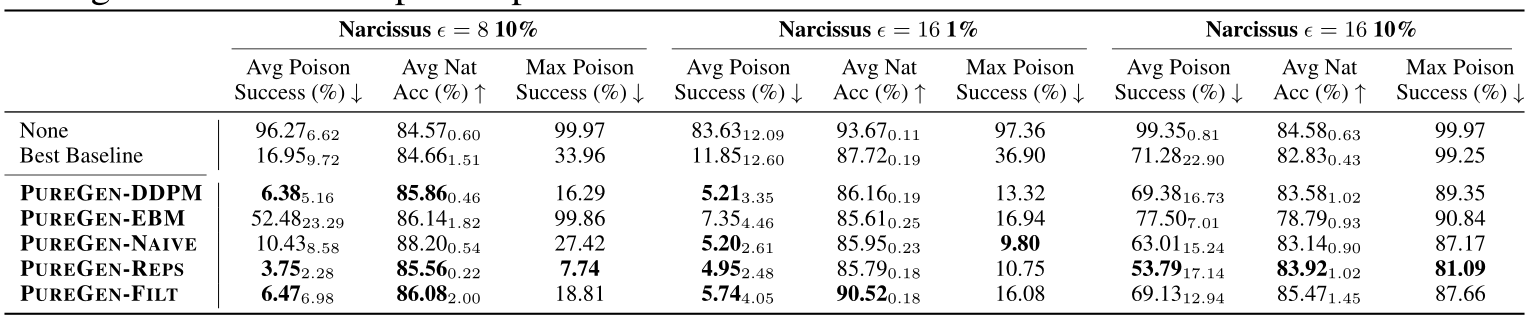

E.1.4 PUREGEN Combos on Increased Poison Power

Table 10: PUREGEN Combos with Narcissus Increased Poison % and

E.2 Additional Experiment Results

E.2.1 Defense/EBM-Aware Narcissus Experiments

To further demonstrate the robustness of PUREGEN, we conduct an additional experiment simulating a scenario where an adversary is aware that PUREGEN is in use. Specifically, we incorporate the Energy-Based Model (EBM) within the Narcissus poison generation framework. Narcissus generates poisons by training a surrogate model, then refining the poison through SGD on frozen surrogate outputs (further details in [4]). For simplicity, we assume that the adversary possesses knowledge of the EBM defense mechanism but is unaware of the specific image instances ultimately used during training.

In this experiment, we include our pre-trained EBM as a preprocessing layer for the ResNet-based surrogate model, using 50 EBM steps—–a choice that balances computational efficiency with reliable performance. When training the EBM-aware surrogate, we freeze the EBM to allow the classifier to train on a diverse set of stochastic EBM outputs. After a brief warmup phase, the entire surrogate model is frozen, and we propagate gradients to optimize poison effectiveness. We test variations of when the surrogate and poison generation do or do not have EBM information, applied to 3 of the 10 CIFAR-10 classes. The results are recorded in Table 11.